| 0:33 | Intro. [Recording date: June 29, 2016.] Russ: Why is ego our enemy? A lot of people I think would say it's our friend. And why would you write a book about it? Guest: I think, ego, I guess maybe to borrow a phrase from your book and Adam Smith is: ego is not very lovely. Right? It's selfish; it's competitive; it's arrogant; it's often delusional or unrealistic. So, again--I'm talking ego in the colloquial sense, not ego in the Freudian sense, which frankly I don't even really understand. The sort of grouping of traits that we might associate with, say, a Donald Trump, or a dictator, or a delusional celebrity, right? I'm talking about the way in which ego ceases to be confidence and becomes delusion and selfishness and all these negative things that ultimately are our enemy not just because they are nasty and unpleasant to be around, but they make whatever we are trying to do harder. If you've lost connection to reality, it's hard for you to make things that people want to buy. It's hard for you to deliver a message in a way that people want to hear. It makes it hard for you to do everything that's already pretty hard. Russ: A challenge, of course, is that as human beings, we all have egos, right? So, it's hard to know. And I don't think you spend--well, you talk about this, not quite explicitly, but implicitly you talk in the book about healthy self-worth, and not just delusional but arrogance, over-confidence. It's hard to know, because it's part of us. It's innate. It's, to some extent just the fact that we care about ourselves. And that's a fact of life. What's wrong with that? Is there any problem there? Guest: No, I don't think there's anything wrong with caring about yourself. I think what happens is when you lose that connection to other people; when you become so obsessed with caring about yourself that you cease to be able to care about other people, for example, or you cease to be able to understand a universe in which, that does not revolve around you--which by the way is the reality. So, I tend to find-- Russ: Well, for you, Ryan, maybe. Guest: There's a quote from Marina Abromovic where she's saying 'The second you start to believe in your own greatness, that's the death of your creativity.' That's because what makes creativity is self-awareness and humility and understanding of the human experience. It's also that hunger to reach inside and connect with other people. And so if ego is this sort of cloudy haze around us, it's makes doing those essential things basically impossible. So, I tend to find that ego can make success impossible; but sometimes egotists will become successful because they are so extraordinarily talented; all the circumstances are right; but then, ego starts to undermine that success that we have and then we will begin toward sort of self-implosion and self-destruction. Russ: We'll be talking about that throughout the conversation. But I first want to ask you why you wrote this book. It's in many ways a strange topic. There's a lot of books about following your passion, 'you can do it'--they really sell over-confidence as a virtue. And certainly major religions of the world tend to encourage humility and humbleness. But most business books don't. And this is more than a business book, but certainly there's a business part of it. How did you come to this topic, and what kind of reaction is it getting from people who are taught often the opposite? Guest: My friend, Ben Casnocha, he's talked about this a little bit. He's said, 'What's ironic about the fact that business books are so encouraging and they tell you to take initiative and you're amazing and special and all of these things is that by definition of picking up one of those books, you already know that about yourself.' You already have that part of the motivation thing covered, at least for a large portion of readers. So, I wanted to write a book that was very different. Like, I say in the intro, 'I hope when you leave this book you think less of yourself.' Russ: Well, I want to buy that book. Guest: Yeah. I realize there's somewhat of an antiviral element to that message. But I also think, if you can leave this book less focused on yourself and more focused on the work and the people who might be receiving that work, I think you ultimately have a greater chance of impact and influence and success. And so, I tried to write a book that I felt that I needed in my own life. I'm not saying I wrote this as some person who has mastered the magical state of egolessness. I'm saying that ambitious people struggle with the side effects of sort of toxic ego. And that's where I wanted to come from, for a minute. And I also think, as a writer your job is to not write the same book that everyone else is writing but to write something different and new. |

| 6:13 | Russ: Can we talk about your ego? Guest: Sure. Russ: So, you've had a lot of success. I don't know how old you are, but I know you're a lot younger than I am. Guest: I just turned 29. Russ: So, you're pretty young. I've seen a lot of my ability to be humbled, to the extent I'm able to be humble, as coming from life's experiencing. Of course, some people have, can cram more life experiences into a short period of time than others. And you've had quite a bit of interesting experience both business-wise and I think as an author. But how do you feel the book has--let's just say the writing of the book--how has the writing of the book forced you or had an impact on your own self-esteem, your own self-awareness? Guest: I'm a big believer in writing books that force you to grow in the course of writing them. I think it would be boring to write about something you know backwards and forwards. So, in writing about ego I'm wrestling with my own. And look, you see this in the process of writing a book. You think a book is going to be about one thing, and you think it will be easy and you'll nail it; and the proposal is rejected. And then the next draft of that proposal is rejected. And the third draft is barely accepted. And then you sit down to write--and obviously I'm not talking about this hypothetically--this is what happened. Then I sit down to write the book that I thought I sold, and it wouldn't write. And so then I had to rethink the entire idea. And then you turn that draft in to the publisher and all of a sudden they don't really like that. And so, writing a book is inherently a humbling experience. And I've had many of those experiences in my life. The bigger the things you try to tackle, the more often you are going to crash into walls and rude awakenings that you sort of have two options in terms of how you respond: you either ignore them and you pretend they don't exist, or you face them and you sort of do that personal work and hopefully you grow from it. And I like to think that I've tried to do the latter more than the former. And so me, writing this book about ego, it was not just an exercise in dissecting and looking at my own, but it really forced me to face a lot of things and look at things. When I sat down and sold this book--I sold it in mid-2014 or early 2014--I was the Director of Marketing at American Apparel. And some stuff happened; and then I was then a consultant to the Board of Directors during the turnaround. But when you watch a company that was once one of the hottest fashion brands in the world sort of implode and destroy itself as a result of the ego of the founder, of the ego of a lot of the long-time employees, of the hedge funds involved, you also see, you know, what the things I was going to try to write about historically look like in real life; and they are not pretty. Russ: This book is a big success; it's doing very well. I think it's--last time I looked, it's one time I think a week ago, it's the Number 100th book on Amazon, which is phenomenal. Of course, you can say to yourself, 'Yeah, but there's 99 books selling better than mine.' But that's not your first thought. Guest: Right. Russ: Your first thought is, 'I got this; I'm on top of the world. My next book is going to be even bigger.' Guest: Right. Russ: How do you restrain--and should you restrain--those feelings? Guest: I think you should. I think it's important that you don't tell yourself a story. Nassim Taleb talks about the narrative fallacy. I think what we can tend to do--an Tyler Cowen has talked about this, too--we see our lives as this grand novel that's unfolding. And in novels, it tends to always work out for the person. Right? We don't see that, 'Hey, this is the high point,' and it's all actually all terrible from here. Not that that's a good way to live, either. But the stories we tell ourselves I think tend to be very optimistic and self-serving. And so, like, with my last book, it had a lot of the same tracking signs and it did really well. But if I told myself that this book was guaranteed to do the same thing, I wouldn't have worked as hard. Right? I think the reason, for instance, the sophomore slump exists is because people take for granted the success of the freshman album or the freshman book or the first project. And, they don't want to look at the work that went into it; they don't want to look at the lucky breaks that they received. They don't want to look at the key people who they owe a great deal of credit to for their success. And so, taking those things for granted, they are rudely awakened when they don't recreate themselves. And there's another quote I have in the book from Elisabeth Noelle-Newman--she's saying basically the only reason to look backwards at things is to find mistakes, not to tell yourself a story about how great you are. And so, I try to do that with my books and with my past successes; but I'm definitely trying to do that right now. Because I have no idea what could happen next week. Or, you know, some Malcolm Gladwell could write a takedown piece that destroys the entire, destroys all the momentum. You don't know how stuff is going to go. And so I think the less you take for granted, the more pleasantly surprised you are going to be as life unfolds. |

| 11:51 | Russ: So, you mentioned Tom Brady, the quarterback of the New England Patriots, in the book as somebody who was drafted very late and had great success. And you [?] actually use it, the example to talk about his team and how they learned from that experience. But let's talk about Brady, and athletes in general. Many athletes use the fact that they were drafted late to motivate themselves throughout their whole career. Like, they have a chip on their shoulder. And I think they actually do have a chip on their shoulder: I don't think it's an illusion or a delusion. I think they actually are still troubled by the fact that when they were younger they were not appreciated or thought to be very good. And I think about you. Okay, now you are two for two. Let's say the next one's a hit. So, the question is: Is there anything wrong with just sort of saying, 'I'm great'? What's wrong with that? That seems like a good thing. It might actually be true. It seems good. I'm a little uncomfortable with the idea that you say, 'Well, I'm great, but I'll pretend I'm not because that way I'll be greater in the next book.' Is that what you are suggesting? Guest: No. I think certainly feeling like you have something to prove is a more productive philosophy than feeling like you are entitled to things. Now, which one goes to personal happiness and contentment better, I'm not sure. But I think what you want to try to do is neither of those things, but just to live in the present moment, to a certain degree. Like, there's a quote that I love from Marcus Aurelius, where he says to 'accept it without arrogance and to let it go with indifference.' And to me that's how I try to live out these things: which is, when you're on top, it's great and you should enjoy it; but you are not letting it change who you are and you are not letting it warp what you are going to do in the future. And then when that 15 minutes is up, or when things change, you understand that that is equally ephemeral as the success. I think that--some people, it's not like, okay, when you're great you should be depressed and find all the bad things in it. It's also that when things are bad, you realize that the success doesn't say anything about you as a person; and the failure or the difficulty doesn't say anything about you as a person. What says something about you as a person are the decisions that you make day in and day out and the actions that you take, at least in my opinion. Russ: Yeah, I think most of us have a terrible time taking that advice to heart. I think it's extremely difficult. I'll give some of my own personal examples in a minute. But I'm curious how you, to the extent that you can, take that advice to heart. So, it's one thing--it's easy to say--and this is a phenomenon that all self-help books have. And my book on Adam Smith has the same flavor as well: Smith will say something like, 'pursuit of money doesn't make you happy.' You ask people about that, 'Of course; material things don't really satisfy; our friendships, our values, these are what create lasting satisfaction.' I think if you did a survey--I assume; maybe I'm wrong--I think a lot of people would agree with that. But they don't act that way. When push comes to shove and they have to make a moral or career decision of family versus work, a lot of times work triumphs; and they may regret it later. Maybe they don't. But a lot of us want to take these things into account. We want to be able to keep our success in perspective. And I'm curious: How do you in your own life try to do that? It's very hard to do. Or, do you just try to write books a lot so that it would be embarrassing if you didn't? Guest: It's--I actually do think that's a nice part about writing a book about stoicism and ego, is that they are sort of public accountability metrics. There are very clear flags that I could get called out on. But, not to talk too much about my own book as, sort of, writing a book is the apotheosis of the human experience, but I'm going through something right now; and Nicky [sp?], who is my editor, and I believe your editor-- Russ: Correct-- Guest: is probably listening, so I'll have to choose my own words carefully. But, so the book sold very well it's first week, much better than I had even expected. Like, the best that--almost more than my previous book had sold in a month. So, that's great. And then, as you know with books, a few days later after the sales are all tallied, the Best Seller lists come sort of float your way. You say, 'Hey, where did I show up on the New York Times Best Seller list? Where did I show up on the Wall Street Journal Best Seller list? And these are things that are nice honors, right? They certainly matter for your ego, and they are validating. But they also matter for your career. It's a nice--it's not just a nice thing that can go on your resume, but they've done some studies about what this quantifiably does to one's earnings, for instance as a speaker, as a writer. Anyway, so, I get the first week's sales and the numbers come back. And I should have ranked very well on the New York Times list. And I did not appear. For reasons unknown. Russ: Surge of anger and frustration. Guest: Yes. And then the Wall Street Journal list comes in on Friday, and I'm not on it at all. And I definitely should have been on that one, and it's much more of a meritocratic list. And looking at the numbers, I should have actually been number 1. I would have been a Number 1 Wall Street Journal Best Seller for the business list. Which is a huge deal. Career-wise. Like, it's not something I need--I've already hit one of those lists so I'm not like, 'Oh, do they like me?' But it's like, hey, if I get this, I'm not buying a boat but it could be nice. Russ: And obviously the fact that it wasn't there is an outrage. Guest: Yeah. Russ: A blow to your ego. Guest: Yes. But it wasn't there because of a categorization issue, a decision that the publisher made about what category it should go in. So, this is both crushing news; and upsetting news; and regretful news. And you have to--this is--I think people think philosophy is what college professors talk about. But it's also, at least for me, this is where it comes in. I can say, 'Accept it without arrogance; let it go with indifference.' But then something happens and you have to decide: can you actually let this go? Like, you need to handle it from the business perspective you need to try to fix this error, you need to find out who is responsible for this error; maybe they need to be held accountable in some way. But, you know, am I going to let this--a day earlier I was elated about the sales, and I was pleased and I think I had achieved some success, to say nothing of the fact that I was proud of the book that I had written. And now this thing that I don't control, an external authority, has, if I allow it to, has the power to take that happiness away from me. And so those are the moments--for me, the philosophy is so valuable. And they are opportunities at the very least to try to practice that philosophy, and it's that internal dialog of 'I can sense you are getting upset. Is this really worth it? Is this going to make you feel better? Is this going to do anything about the problem?' And those are the moments where, easier said than done meets well argued [?] try to do it. |

| 19:48 | Russ: So let's say I've got this problem, which we all do, of failing to accept--did you say it was Marcus Aurelius? Guest: Yes. Russ: So, I want to live like Marcus Aurelius. And I tell myself that I'm going to live like Marcus Aurelius. But when I don't see my name in the list, or my book in the list, or my kid on the roster--whatever I need for my pride and self-satisfaction--I don't get the raise, I don't get the promotion--I can tell myself that, but often I can't act that way. I can say, 'Oh ,'--well there's sort of two levels for me. One is to remember to be mindful of the idea of what you want to be; but often that's not enough. Do you agree or you disagree? Guest: I absolutely agree. Like, look, you could be the most stoic, self-controlled person. But if someone walks up to you and punches you in the face, you might have a sort of immediate physical reaction. You are going to get an adrenaline dump. And maybe you fight back a little bit. But, what you probably do have the power, or hopefully you do, is that when that person's on the ground or you are going to kick them repeatedly, you--it's not about having a flawless, perfect reaction to everything. And I think trying to pretend that that's possible is silly. It's, 'Okay, at what point in the tantrum or the over-reaction or the defensive posturing can I stop myself or get ahold of myself?' There's another line from Marcus Aurelius where he's saying, sort of, 'When jarred unavoidably by circumstances, revert back to philosophy and to what you know.' And I think what he's saying is: Your temper is going to get the best of you; your fears are going to get the best of you; your emotions, your hormones, all these things. But, you know, just make sure it doesn't go too far. I don't think the Stoics genuinely believe that you can quench yourself of sadness when someone you love dies. But, you know, the choice whether you are going to be devastated by grief for the rest of your life, that is within your control. And that's where you can do work, and ideally as you experience more and more things, you get better at it. They call it philosophical exercises, and I think they mean that exercise literally: it's a muscle you're building. |

| 22:20 | Russ: So, I agree with part of that. I'm going to try a different reaction, though. I was watching Chef, the movie, last night. There's a great scene in that movie where the chef confronts a food critic who has been criticizing him and he's screaming at him, and of course they record him and it goes viral. But he's screaming, 'You don't get to me. You don't bother me at all.' And he's telling himself that, but he's failing miserably. And I think talk is cheap. I think it's credibly difficult to avoid these kind of emotional reactions, especially to our ego, and especially to issues of letting go of control and expecting and demanding internally in our narrative about ourselves that we are in control, and when things don't go the way we want or expect, really having a hard time dealing with that. And I do think it's a matter of practice. But I think if you don't have a strategy, I think you fail. I can't tell you how many times--I think we've all experienced this. We see a movie, we listen to a lecture, we read a book; and it makes an impression; and we say, 'Yeah, I want to x'--be a better father, be a better husband, be a better friend, be a better colleague, be less concerned about my ego. And we fail. Once you put the book down, I go back to being my "true self." So, for me--there are two things for me that help me do this. And it's hard to talk about this without sounding like you're bragging, because we all fail over and over again at this. But for me, what I try to do to help my own focus is I live a religious life, which--I would never say this [?] 'Oh, you should believe in God; that way you'll be more humble.' That's not a marketing technique and it's not good advice. But it does have an impact. But the second is meditation and thinking about times when my own set of issues comes up, and meditating on having a focus and attention to react the way, say, you are talking about: trying to be more indifferent to failure and not to overreact to success. And I find that--I think; it's hard to know--I think it has some impact. Do you do anything like that? Guest: Yeah. I like what you're saying. I think a lot of what we are talking about is not about what you're doing in the moment in the same way that sports--it's partially what you're doing in the game but it mostly has to do with preparation because it's just the body reacting, these sort of split seconds. So, I tend to do a lot of thinking about what can go wrong in advance. So, you know, this best seller list thing--this is not an outcome that I had wholly unconsidered, that was fully unconsidered. I thought--I expected not to hit the New York Times list; I figured that the Wall Street Journal might not happen. And in fact the bitterest pill of it for me to swallow-- Russ: Sorry for laughing-- Guest: No, no, no. Sometimes you have to laugh. Russ: I'm laughing as an author who has never been on either one. So, go ahead. Keep going. Guest: But the bitterest pill for me was actually the part that I had not considered, which was that I might not hit it, like, not hitting it because of their capricious, arbitrary standards is one thing. To have not hit it because of avoidable error that was, I didn't think about--that was the hardest part. So I think preparation, like the Stoics are big on negative visualization, thinking in advance what could go wrong, but on one hand what you could do to prevent it; on the other hand to just be personally aware. It's too hard for me to sit still to really meditate as much as I want. But I try to incorporate sort of stillness and quiet more in my life as I've gotten older. Like, I did this talk yesterday at a running store, and I was joking that we have a pool at our house and I'll get in it with my wife and all I'll want to do is swim laps. And she'll joke, like, it's being in the pool that is nice. You just have to be in it. You don't have to do anything. Russ: Accomplish. Check 'em off. Seven laps. Eight yesterday, but nine today. Guest: Right. Right. And so I'm trying to cultivate some of that stillness in my life, which I'm hoping helps me think a little bit more calmly and serenely, that I can return to that stillness in situations that are--I think one of the things that people forget is that, oftentimes when things go bad, like this thing happened or some other thing, you'd think it would be very painful. But depending on how you orient your life, it can actually be really exhilarating because you can go into a crisis chaos mode. And there have been times in my life when I've really thrived on that chaos, and I'm just rolling calls on the phone and I'm sending emails and I'm plotting and scheming. And instead of dealing with my feelings, I'm just sublimating them into a series of somewhat pointless activities. So I'm trying to cultivate a little bit of not doing that in my life, like, and have a set point. Russ: It's very challenging. It's sort of a lifelong mission to try to restrain one's emotions, ego, sense of control, etc. In one sense--you could argue--I don't know if this is fair or right, but you could argue it's in many ways the essence of growing up. Which is why it's interesting that you wrote this book at 29 rather than, say, 59 or 79. It's a book of an older person in general. So, one could argue you do have a whole lifetime to become an egotistical maniac before then realizing you forgot the lessons of your own book. Guest: Yes. Hopefully not. Russ: Yeah, we hope not. But I do think it's a fascinating challenge of behavior and habit formation and just success generally in life, to implement the things that you want to implement. Even--the fact that you think something is a good idea, it's remarkable to me how little that actually has to do with whether you actually live your life that way. Guest: Yes. I guess maybe a way to put that is: Wanting is not nearly enough. Imagine people that you've met, and that I've definitely met, that are, 'Oh, I want to write a book.' And it's like, I want to do a lot of things. Wanting is not what makes things real. It's the doing and the commitment to the doing that sort of separates the idea from existence. Russ: Yeah. 'I want to spend more time with my kids.' Guest: Right. What are you actually doing? Russ: Yeah. What's stopping you? Russ: Very challenging. |

| 29:51 | Russ: Why are you--to get back to the book, and I apologize for that long behavioral digression--you are very high on the Civil War general, Sherman. I don't know much about Sherman. I learned a little more about him from your book. I've never read a biography of him. I have a very negative thought about him. Guest: Are you from the South? Russ: Sort of. I'm a kind of Southerner. I was born in Memphis; I only lived there a year. But I think--I'm pretty sure it's not my southern roots. The only thing I know about him is that he marched to the sea and burned his way through the South, and just destroyed a lot of stuff. And he was successful. That's all I know about him. But you have a lot more to say. So, tell us why he's a person worth understanding. Guest: I'm just generally fascinated by the Civil War. It's one of those things that seems very simple, and then you study it and it becomes very complex. And then it becomes sort of simple again; and then it becomes infinitely complex again. So, I've just gotten a lot of joy and fascination studying the Civil War. And I like Sherman because he was sort of the least sure of himself of all the generals. Like, if you compare him to General McClellan, they are polar opposites in every way. Like, McClellan was born to be a general. He studied in France; he was number 1 in his class at West Point. He wrote a book on Napoleon. He was just--he was called the little Napoleon, 'the young Napoleon', I think was his nickname. But anyway, he was going to save the Union. He was Lincoln's man. He was in charge of the Army of the Potomac, which was supposed to protect Washington. And he just repeatedly failed. Russ: Utter failure. Guest: Utter failure, in every single way--to an absurd--and managed to alienate and piss off every person who believed in him. There's a story where Lincoln came to, needed to meet with him so he went to his house; McClellan wasn't home. And so Lincoln said, 'Oh, I'll wait in the living room.' And he sits in the living room and McClellan comes in, sees Lincoln in the living room, pretends not to see him, walks upstairs and goes to bed. Which is just amazing. Like, if he had actually been good, I wonder what America would have become, because he may have actually been a Napoleonic ex-figure [?] in that he might have usurped democracy and stuff like that. But anyway, Sherman was the opposite of that. Sherman's father died when he was young; he was adopted. He did okay at West Point. He missed the Mexican-American War. And then, he was given a subordinate command in the Civil War. And basically no one thought he was really going to amount to anything. In fact, he was basically kicked out of the military for his sort of scare-mongering--he was convinced that the United States would need far more troops; that the war would be nasty and terrible and go on for years. He was basically dismissed as a crazy person. So, like, you know, you read about a Napoleon or a McClellan and what they have is this sort of certainty--like they believe in this destiny that they were meant for greatness. And then in some ways they achieve that greatness, or they approach that greatness. Sherman was this person who was sort of crippled with self-doubt almost all of his life. And yet, he accomplished more than almost any of those figures. And there's this wonderful quote I have from B. H. Liddell Hart, who is a brilliant military historian and strategist in Britain in WWI and WWII, and he has this passage where he's talking about the difference between those type of people, and how, in a weird way, accomplishment must be so much sweeter to someone like Sherman because he never thought it was his by birth. That he was actually experiencing it as it was happening. And so I was fascinated by that. And then of course as strategist I talked about him a little bit in The Obstacle Is the Way: he realized that the entire concept of a large army attacking another large army was just a recipe for pointlessly killing a lot of people. And his march to the sea was in many ways a repeated evasion of pitched battles against the Confederate Army. And he destroyed a good portion of the South, but not indiscriminately. It was not total war by any sense. What he said he was doing, he would 'bring the hard hand of war to the South.' And what that meant is, the original Northern approach was, 'Hey, if we just wait this thing out, the South will eventually give in.' And, you know, weirdly, a lot of the battles in the Civil War are in the North. Which makes no sense, right? Because the South was trying to leave the United States. And Sherman realized, 'Hey, this war has only been able to continue because the Southern people have not felt any of the consequences of supporting secession. And I'm going to bring that war to them, and I'm going to make them relent.' And that's basically what his march to the sea did: it crushed the economic viability of the South. Which by the way he had predicted from Day 1 in the war was the only way to win it. And he did that--he also was brilliant enough to understand that it wasn't until the North took a number of major Southern cities back that Lincoln would be able to win the re-election. So that was a critical, another point in American history. So, I just find him to be a fascinating figure. Russ: But do you think his humility is an important part of his success? Or do you think it's just that he had the blessing of having a sort of military silver spoon of expectations that just happened to make him more humble? Guest: I think it's both. But what I think is so interesting--I talk about this in the book--is, after the Civil War, Sherman famously--basically the Presidency was offered to him; and he gave his famous, Shermanesque statement: he said, 'If nominated, I will not run. If elected, I will not serve.' Basically: Leave me alone; I've done my--he said, 'I have all the rank that I want.' So, I'm so fascinated. Of all the Civil War generals--basically he retired; he served a little bit more; he fought in the Indian Wars and then he basically retired to New York City and he watched Broadway plays for the rest of his life. Russ: My kind of guy. Guest: He seemed to have lived a somewhat satisfying life; and the success did not ruin him, in the way that Grant was pushed toward the Presidency in a way that was disastrous, and he was pushed toward Wall Street, which was disastrous. So, I just find him an interesting model. And I think it's unfortunate that more people don't know about him and look to him in that way. |

| 37:15 | Russ: So, let's take the flip side of that character trait, and let's look at Winston Churchill. Guest: Yes. Russ: And Winston Churchill, you talk about in the book. But he had, it appears, an enormous ego-- Guest: Yes-- Russ: that sustained him through all kinds of failure. He was blamed for some of the-- Guest: politically-- Russ: Politically, in the first World War. And in the run-up to WWII he's considered a crazy lunatic who is worried about Nazi Germany. And ultimately his reputation is redeemed and he's considered one of the greatest figures of the 20th century, like top five. So, his ego--and by the way, you quote, I think, the Manchester biography, Volume 2 alone. Well, in Volume 1, one of the moments that's legendary in my household because my kids loved it so much--you know, he escapes from a prison in the Boer War, walks a huge distance, I forget how far, and presents himself in the middle of the night at the British Embassy and pounds on the door and someone opens a window upstairs and says, 'What's going on?' And he yells up something like, 'It's Winston Bloody Churchill. Open this door.' And so, here's a man who is totally full of himself, as far as I can tell. And he's a great success. So, why is ego the enemy? Guest: I'm fascinated that you would ask this, because--and for our listeners, we did not plan this--I am actually in, I have like 10 pages left, in Volume 2. And I read Volume 1 in the last couple of weeks. So, I've been reading about Churchill, and he's fascinating. And the Manchester biography is so great, because he looks at that ego; and he says over and over again, basically Hitler and Churchill were opposite sides of the same coin. And he says--it's interesting, maybe the only reason that Churchill saw through Hitler was that he saw a bit of that megalomania in himself. Russ: Yep. For sure. Guest: So I've been very interested in that. I'm not saying that egotistical people never become successful. But, in Churchill's case, yes his ego fueled his ambition especially early on and got him ahead. But, you know, not all the things that happened to him was he wholly without blame for. Russ: Correct. Guest: Part of his exile, where his middle [?] where he is alone is not just the result of Neville Chamberlain being delusional about peace in our time. A lot of it had to do with the fact that Winston Churchill was without allies and managed to alienate and hurt the feelings of pretty much every single person that he needed their support. And, you [?], like his wife is, basically, 'Winnie, don't do this. This is not a hill to die on.' And he's like, 'I have to defend the King's right to have an affair and marry a commoner,' or he got bogged down in the fight about independence for India. And the Gallipoli Campaign was a stroke of strategic insight; but then sort of Churchill figured that just having the strategic insight was enough. Actually executing on that idea and managing was something he wasn't quite as good at. And so, what's so fascinating about Churchill was he was this immensely creative, innovative, brilliant guy. But the problem was he believed in all of his ideas equally well, with equal certainty. Russ: Correct. He had a tank for the landing that was a total failure--I can't remember any details about it--a landing craft. He made a zillion mistakes, right? Guest: Right. Russ: And we also have to add--his History of the Second World War, which is a phenomenal--I think it's 6 volumes, 5 or 6 volumes--is of course marred by the fact that it's all about him. Guest: Sure. Russ: Or, it's like the chapter in Nietzsche, I think it's in Ecce Homo, it's like 'Why I Am So Smart.' That could have been the title of the book. So, he's a man who has a tremendous ego. And yes, I'll accept the point that he could have been more successful, had he been a little bit more self-aware. But maybe not. You know? Guest: It's interesting because I was just reading that one of the reasons that the Cabinet was so reluctant to have Churchill be involved in some of the pivotal negotiations and discussions before Churchill came back to power, one of the-- Russ: They were afraid of him. Guest: And Neville Chamberlain actually says, 'Oh, he's just basically here to write another book.' That's what they thought he was trying to do. And so, it's not that he could have been more successful: it's that the ego that propelled him to greatness was also, could have equally destroyed him at any moment. And in fact I would say Western civilization is lucky that Winston Churchill had his ego in check just enough that he never fully imploded and took his ball and went home and did something so foolish that, you know, that he ruined his chance of ever coming back. Russ: And you talk about this--how we only see the successes; we don't know how many egomaniacs fail because they couldn't restrain their ego. I think, for me, Steve Jobs is another example--and you talk about him--where, Walter Isaacson's book portrays him, I think--it appears honestly--as an incredible egomaniac. And I think a lot of people misread that to say, 'And look how well it served him.' Because he's a great success. But I see someone who came this close to someone who became a totally ignored figure in American business history. Guest: That's exactly right. Russ: So, talk about that. Guest: That's right. The fact that he came back to Apple obscures how unusual and unlikely that is. Nobody gets a second chance like that. I think that's interesting. I'm fascinated by just the sheer pointlessness of it. Like, he was famous for parking in handicapped spaces in front of Apple, right? Russ: Yeah: what's the point? Really. Guest: And I just--if you think--it's like--so, you could have redesigned the entire headquarters so you had a parking spot in the front. You're a billionaire. You could have paid for someone to park your car for you; you could have had a valet. You could have walked 10 feet. So in some ways it's this dark personality flaw. I imagine he perversely--it's not that he just did it and he didn't realize it. I get the sense that he probably perversely enjoyed that. Russ: No, I think that's exactly right. I think that's the most destructive part of ego run amok, which is not just that it limits your ability to have people work with you or whatever. But it corrodes your soul, which makes it much harder for people to work with you. Because you revel in the fact that you're important and they're not. It's just a horrifying human temptation that is--we talked about before--it's challenging to avoid. Because it feels good. |

| 44:57 | Guest: Have you read Robert Caro's series on Lyndon Johnson? Russ: Funny you mention that. I was just thinking about that as we were talking about Churchill. Because that book, to me, is the greatest single portrait of human ambition, and the urge for power. It's one of the great achievements-- Guest: In all of Western literature. I think it's stupendous. Russ: I think it's the top 10 book, ever. And it's still going. Incredibly. But yeah; there's a book where, especially Volume 1, you see the naked arrogance of Johnson on display. Russ: And I guess one thing we haven't talked about--I'm not sure you talk about it much in the book--is how often people who are egotistical on the outside are fundamentally insecure. Guest: Yes. Russ: Which I think people find "surprising." It's not surprising to me at all. It's clearly a defense mechanism, a shield. I see it in my own self. I think part of the thrill of getting a little more humble as you get older is realizing, being able to see yourself honestly, and what you were like when you were younger. And it's not pretty. Guest: Well, one of the things that Caro says in the book that I like is, he's saying, you know, it's not that power corrupts: it's that power also reveals. And I think that's what you see with someone like Steve Jobs, is that, as he became more powerful, he wasn't becoming better: he was becoming worse. Even as he was becoming more and more talented and creatively brilliant, he was becoming in some ways personally more repugnant. But what's so fascinating to me about Johnson, yeah, is that he was immensely insecure; and it all sort of came down to the failure of his father and the struggles that the family had. The revealing scene to me was that, Caro talks about, in college Johnson had this reputation of sort of bullying everyone. He would call you out; he would stick his finger in your chest. And there was some poker game where somebody finally had enough and they stood up to fight Johnson. And Johnson sort of threw himself on a bed and stuck his--he started kicking his legs around, and Caro says, basically like a girl; and saying 'If you come at me I'm going to kick you. If you come at me, I'm going to kick you.' And so you realize just sort of how fragile the edifice can be. And I think it's fascinating, Donald Trump is talking about ego and, you know, he says 'Every successful person has a big ego' and 'America is being out-egotized.' And then this guy can't not respond to random trolls on Twitter, as though that's a sign of strength. And, [?] I talk about that story in, between Angela Merkel and Vladimir Putin, in the book where Putin attempts to intimidate her by letting a dog run into the room that she knows she's afraid of. And for her, what I admire, is her not rising to that bait. And resisting and sort of enduring a tiny bit of immediate discomfort for a larger goal. For me, that's bravery and strength. And that's where confidence comes from. Not, 'Hey, I'm going to say something mean about this person on the Internet when I get back to my phone.' Russ: Yeah. I think that's the challenge of, really, your ego in everyday life: the petty humiliations that life inevitably delivers to all of us. And how you accept them, react to them. |

| 48:35 | Russ: There's a story I wanted to mention. This is a good time to mention it. It's by Isaac Bashevis Singer. It's called "Gimpel the Fool." It's one of my favorite short stories. And it's remarkably provocative and deep, at least--if you think about it on the surface, it's very straightforward. It's about Gimpel, whose wife betrays him; his friends deceive him. Everything in his life is horrifying. He's a sucker; he's a victim, over and over and over again. And he just reacts with--he misreads all of it. And that's why he's Gimpel, the Fool. But the title is fundamentally ironic. I think. In terms of how we deal with betrayal, how we deal with those petty humiliations: His are not petty. But that's what makes it more powerful, a more powerful story. And when that person mocks us on the Internet--actually, let's turn to that, because I wanted to ask you. So, Adam Smith talks about the quackish arts of self-promotion and how you should avoid them. And in our time, they are everywhere. So, you mentioned Twitter, or Facebook. How do you deal with that? What is both the positive and negative? I think it's very hard not to get excited when you get a Follower or a Friend or a ReTweet. And you become a little bit addicted to that adrenaline rush. Or dopamine; I guess it's dopamine. Guest: That's exactly what it is. I'm ashamed of the days that I've lost in my life, where something has gone really well--like I've written an article and it's sort of blown up online, or I got some decent media placement; and I've just spent hours sort of refreshing and looking. You are basically just high, is what you are. And you are enjoying it. Russ: You are just a rat. You are just a rat, hitting that buzzer, getting that cheese, over and over. 'Oh, another piece of cheese.' Guest: And it's silly to think, 'Wait, something good happened, and so it's costing me'--like 'I'm not able to work today, because something good happened.' It's absurd. On the other side of that, one of the things I've realized is, occasionally from time to time, especially more when I was working more for companies, you have unpleasant email exchanges with someone. Right? They've done something wrong? They think you've done something wrong. And you're arguing. And I remember I was in some argument with someone, and it stopped all of a sudden. And I couldn't figure out why. And I found out a couple of like weeks later that I either accidentally marked the email as 'Read' or my Inbox had eaten it. And so, like, that nasty thing that I then found and was made upset by, I'd narrowly missed being upset by. Right? And so I just realized-- Russ: You could choose to do that. Guest: Yeah. When I get the sense that someone is just trying to get the last word, I don't consent to that. I just go: 'Oh, I'm not going to open this. I'm just going to pretend that I didn't receive it.' And that has saved me so much unnecessary pain/anger toward someone. And then it dies off, and usually you are fine talking to that person again. Russ: You have to rise to the next level. You have to rise to the next level and say, 'I'm going to give you the last word.' It's okay. It's really okay. I love it when I'll say something on Twitter and someone will challenge me back and ask me a question, and I forget about it. I don't respond. And this happened to me yesterday--somebody writes me, like, 6 months or a year after a previous Twitter--he says, 'You never answered my question. You don't have an answer.' And I'm thinking, 'Do you really think that's the only reason I might not--' but they do. And I'm going to enjoy the fact that I'm not going to play that game. I think it's a--I don't know if it's a form of self-deception, of the good kind, maybe-- Guest: yeah-- Russ: to say, 'I'm not going to play that game. I don't have to play that game. I can just watch it and observe it and be above it. I'm not going to play.' Guest: I wish there was an--and this is going to sound a little bit egotistical, but I wish there was an acronym that I could use that basically--I was talking to someone about this the other day--that, it would basically be, like 'Not Enough Followers to Respond.' So, like, when someone with 7 Followers says, like, you know, 'You're worthless. I hate you'-- Russ: Your book's garbage. Yeah. Guest: Yeah. I would just be able to say, 'Hey, yeah, I saw that you said this, but I'm not responding.' You know what I mean? So they don't think I'm ignoring them. Russ: Yeah. No. Exactly. Because if you don't respond they get a moral victory. Guest: Yes. Russ: But again, I think you go to the next level. You say, 'It's great. I'm going to give them that moral victory. They're pitiful. Their life is so empty that they have to get a thrill from insulting me.' Right? So, I'm going to say I feel sorry for them. And I do. I don't want to suggest this is, again, some little formula that you should tell yourself. I think you should actually think that's sad. You don't have to respond to it. And let them have that. Even let them have that moment of glory, if they think they've made a fool of you. It's really okay. What I find fascinating is how viscerally I sometimes want to respond. And, I've tried to re-make--and I don't know if this works or if it's a good idea--but I've tried to re-make my reward function to be more about enjoying not responding. Which is--it took a long time. Guest: One of the responses I've found that works decently well, especially because these things can be a little contagious. So, it's not, all of us, if you don't respond to these things enough times it can start to take on an appearance of truth: like, let's say that some rumor-- Russ: Right; sure. Guest: Or just say, like, 'I hope this makes you feel better.' And, you know, that usually puts it in its proper place. Which is: This has really nothing to do with me and everything to do with you. Russ: Yeah. |

| 54:38 | Russ: So, here's a related example, which you talk about in the book, which is the challenge of admitting that you don't know something. Guest: Yeah, sure. Russ: And it took me forever to be able to say, 'I don't know,' and enjoy it. So, most of my life-- Guest: You talk about that in How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life . Russ: Yeah. It's so important. First of all, the temptation to lie. You asked me if I knew the Caro book. Now, I happen to have read--what I didn't reveal--is that I'm a huge booster of that book to my friends. But I've not read Volume 3 in its entirety. I kind of bogged down. Right? But when you asked, I didn't say, 'Well, I've read two of the books.' You didn't ask me, literally. You asked if I'd heard of it. Guest: Right. Russ: So I answered the truth. But I don't like to say that. I want people to think, how he's read it--all four volumes. And I haven't. I've only read two. And to say I haven't, hurts. Which is pitiful. I mean, it's such a trivial, stupid thing. Guest: Right. Right. Russ: But when we talk about self-awareness--I don't know whether it's the way I grew up; I don't know whether it's my genetics; I don't know whether it was parenting--but my parents, it took me a very long time to say 'I don't know.' And I know people who don't have that problem. They can say it; and they seem comfortable. For me, it took a long time to be able to say it. And it's taken a much longer time to actually kind of enjoy it. It's okay. It's not just okay: It's liberating to say it. It's great. You don't have to know everything. Guest: I've found--I think for me what helped sway me in that regard--and I'm not very good at it--but it's like, I went out to dinner--or lunch--with this very important person. And I realized after I left that I'd talked the entire time. When really, I should have been learning from this person. And I realized that was sort of a nasty habit of mine. Russ: But they were so impressed, Ryan, with those brilliant things you have to say that it turned out to be a wonderful decision on your part, wasn't it? Guest: Yeah. And look, this guy had said--I'd asked him some questions that he'd responded, 'I don't know,' many times. And I realized that, I realized that whatever the perception was, the real sort of power differential was in the fact that he was comfortable not talking, and I was only comfortable if I was talking. So, in fact, saying 'I don't know,' or not answering or not talking is not weakness: it's the opposite of weakness if you do it right. You know? And so that's, sort of seeing that; and there's other people that I admire, like if you've ever checked out Tim Ferriss's podcast-- Russ: Sure-- Guest: People will say things, and he'll say, 'Wait. What is that?' And I'll even cringe little bit listening. Russ: But he doesn't know? Guest: And it's like, oh, he's admitting that he doesn't know in front of millions of people. That's--I find that very inspiring, just as you are saying. And also as you said, liberating, because you are not keeping up this whole front of knowing all this stuff. There's an Epictetus quote--he says, 'One cannot learn that which they think they already know.' You also can't learn what you pretend to know because no one is going to teach you because they think you've already got it. Russ: That's a great point. Well, I want to give you some consolation, which is that you are not humiliating yourself in front of millions of listeners when you just talked about how much you talked at that lunch. It's only tens of thousands, so it's not so bad. That's our flaw, if we're not careful, that we become egotistical about our humility. So, here you and I are, to some extent, bragging about our humbleware[?] if we're not careful. Any thoughts on that? Guest: I think you are always wanting to look at the practical utility of it, right? So it's not 'Hey, you come off bad when you talk the whole meeting.' To me, it's like, 'I went to this meeting with this person I'm probably going to never meet again, and instead of learning anything, I sucked all the air out of the room.' I don't want to do that in the future because it's depriving me of something. So it's--you know what I mean? I think you want to make sure--humility is not great because of how it makes you look to other people. And I think Adam Smith talked about this so well in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, and I think the Stoics talk about this a lot, and I love that you talked about it in your book: it's like, these things are good for their own sake. That there's a selfish reason to be good and to do the right thing and to be humble is because the alternative is hurting you in ways that you don't understand. It's making you feel pain that maybe you don't understand, and it's shutting doors that would otherwise be open if you were different. And so me that's the reason I think you want to think about these things. So, I hope it doesn't come off as bragging and more comes off as sharing tools or strategies. Russ: Yeah. I agree. I have to get in this quote from C. S. Lewis, just because it belongs in this episode and I don't want to miss it. He said, "Humility isn't thinking less of yourself. It's thinking of yourself less.' Guest: Yes. Russ: So, it's not about that you are constantly berating yourself for your character, your flaws. It's that you are not the center of the universe. Guest: Yes. I heard Nassim Taleb once say it's not that God is great: it's that God is greater than you. And I liked that. Russ: That's certainly true. |

| 1:00:29 | Russ: I want to shift gears--we've got a few more minutes; we're close to out of time but if you have another minute I want to try something really different. One of the things I thought about while reading your book is the role of ego in non-profits. A little bit of a different twist on some of the lessons. So, one of the things I've noticed when I look at nonprofits it's--they all struggle with--essentially it's an ego problem. That, the people who run it often forget what the mission is. And I guess they start to think it's about themselves. I don't think they literally think it's about themselves. But something happens. So, instead of trying to cure the disease or help the poor, whatever it is, they start to make decisions to make the organization, say, bigger--but not any more effective, or maybe less effective. So, they'll get a donation typically earmarked for some purpose--it's really kind of tangential and distracts the leaders from the mission of the institution. So they take the money, and I'm thinking, 'Why are they taking that money?' Guest: Right. Russ: That's not the goal. And they take it because it makes them feel important to have a bigger organization; they want to stroke the ego of the person who gave them money; they convince themselves incorrectly that they'll get more money out of the person down the road, maybe. I don't know if you've ever thought about that. I just find it fascinating, to me, how hard it is for nonprofits--who often have a measurement issue: it's very hard to assess whether they are achieving their mission--have trouble with that kind of--I think it's an ego problem. Guest: I absolutely do--I think it's the temptation, what your station or what you are working on says something about you as a person. William MacAskill's book on effective altruism is a sort of a very objective look at these things and I think your sort of always remembering that as good. There's some story I remember about George Soros--maybe it's apocryphal--he says, 'What are we going to do with my money? This is my money.' He's saying this about a charitable donation. And someone said, 'You know, it's not yours--it's half the people's. In the sense that, just because you created a foundation, that money would normally go to the government; and so it's reminding yourself, I think, that this is yours in trust. You don't actually own this. This is not yours. You are exploiting--you are taking advantage of a loophole that the people have given you. And I think maybe you think about it that way--that you are the servant of a cause rather than the head of an army or however an egotistical person might look at it. Russ: Yeah, but come full circle--to our earlier discussion of how you bring these lessons home, given how frequent this challenge is, for the nonprofits I've looked at and come into contact with, it must be hard for them to remember. You'd think it would be easy--you think, oh, you're working with this charity; it's a wonderful organization; and they are trying to do this great thing. And yet, you lose sight of you the fact that you are really holding something in trust, whether it's--I don't find the tax money so exciting, but that's okay. But I do find the cause exciting. And you can't keep that in mind, somehow. Something goes wrong. Guest: Well, I guess it's a good reminder that ego is manifesting itself even in the clergy and in nonprofits--what you as a musician or you as a celebrity or you as a high-powered CEO (Chief Executive Officer)--you better be aware that it's going to affect what you do as well. Russ: Yeah, for sure. Well, any closing thoughts? Any closing advice on what people might take from your book? Is there a lesson from the book we haven't mentioned that you want to highlight? Guest: I don't think so. It's really been an honor to talk to you. I'm a huge fan of your work, so this is very cool. And Adam Smith was a huge influence--there's a quote from him opening the first--Book I, Book II, and Book III; and I guess if I could leave with anything it would be to reference what I took the most from your book is that idea of the indifferent spectator, impartial spectator: like, hey, I'm going to look, I'm going to use this; I'm going to create this external thing that allows myself to see myself a bit more clearly and objectively and let that guide my behavior so I don't do things that I would otherwise be ashamed of. |

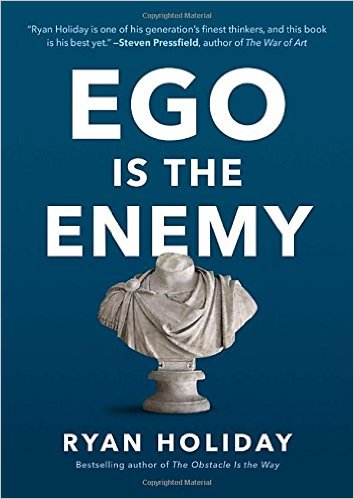

How does our attitude toward ourselves affect our success or failure in the world of business or in friendship? Ryan Holiday, author of Ego Is the Enemy, talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about the role of ego in business, our personal lives, and world history.

How does our attitude toward ourselves affect our success or failure in the world of business or in friendship? Ryan Holiday, author of Ego Is the Enemy, talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about the role of ego in business, our personal lives, and world history.

READER COMMENTS

Jerm

Jul 18 2016 at 3:50pm

Aww…he made an explicit connection between the ideas in his book and Trump. I was hoping it would be the theme not directly said (as it was with previous guests).

Fun episode. Stoics don’t get much press, but I guess that’s part of the deal.

John G.

Jul 18 2016 at 6:52pm

Ironically, or not, the C.S. Lewis Tweet for today is:

“If anyone would like to acquire humility, I can, I think, tell him the first step. The first step is to realize that one is proud.”

jw

Jul 18 2016 at 7:49pm

– Right off of the bat “The sort of grouping of traits that we might associate with, say, a Donald Trump, or a dictator, or a delusional celebrity, right?” was unfortunate. Falling for the narrative that only Trump had an ego and grouping him with dictators and delusional celebrities was wrong. He may want to refer to today’s Cafe Hayek (here) on the question of the ego required to endlessly pursue political power like, oh I don’t know, the Clintons?

– Long time comment readers will note that I constantly criticize public and government figures for excessive hubris. But I feel that some personality types express themselves best with an aura of excessive ego while others work and fit in best as the quiet professional. Also, armchair psychoanalyzing LBJ as an example of all egotists was too simplistic. I have know great people who others might mistake as overly egotistical, but in truth were merely being themselves and were very nice people. Of course, there are many, many examples of excess, but trying to stereotype is extremely difficult. One size doesn’t fit all.

– Stoicism might best be exemplified by Marcus Aurelius, but there were many failed Stoics as well. There were many competing philosophies in ancient Rome, and Stoics never made their case to become a dominant philosophy, and still haven’t in the 2,000 years since.

– I don’t see how his message is going to get out in the current Kardashian driven celebrity culture we live in now, with accomplishment free millions available if you can blow your horn loudly enough. Like NBA dreams, this only works for a tiny minority, but affects the perceptions and actions of millions who try and emulate them.

– In other cases, again with respect to our current culture, others feign a bombastic ego in order to establish and extend their personal brand, then go home to lay on the couch with the kids and watch “Sesame Street”. It would be hard to recognize and differentiate these people from their public personas.

Abe

Jul 18 2016 at 11:10pm

Let me take an armchair psychology crack at explaining the sort of egotistical behavior described in this podcast.

First of all, this was touched on, but a high estimation of one’s abilities seems to be a somewhat separate issue. If you asked LeBron James if he was the greatest basketball player in the world, he would probably say yes, but that’s not egotistical. It’s just true. In fact, if he said no, and he believed it, it might even cause him to make some very irrational choices. So I will offer a different description.

This sort of behavior and worldview is a rational response to having a great deal of uncertainty about your ability. There is a high cost to mis-estimating your ability, so narcissism makes sense: refining estimates of your own ability is a high-value activity, but his mainly consists of thinking about yourself. Both insecurity and arrogance make sense: insecurity stems from believing there is a real possibility you have very low value, and arrogance comes from believing there is a real possibility you have very high value. It’s worth it to pretend you are both high-value and low-value, then, if for no other reason than to see if others are convinced.

This “model” for this type of behavior implies some things about the world. For example, we expect older people to display less of this behavior, since they in general have less uncertainty about their ability. They have a lifetime of data! Also, since they have a shorter working future, mis-estimating their ability has a lower opportunity cost. It does seem that older people exhibit less of this behavior. It would also seem that this behavior would be more common among people who do work with few opportunities for objective external assessment. So this behavior should be more common among artists and politicians than among athletes, for example. I don’t know if this is the case.

To me, this is compelling, but not convincing.

Jeff W

Jul 19 2016 at 11:33am

If Holliday’s thesis is true, why is it much easier to name people who have YUGE egos and are successful in their pursuits? Russ and Ryan discussed Steve Jobs, Winston Churchill, and LBJ as egotists, and then gave us a general from 150 years ago as the positive example of someone with adequate humility.

It seems to me if Sherman’s March to the Sea had embittered and emboldened Confederates to prolong their resistance, we could call Sherman an egotist as he was delusional in thinking he could bring the South to its knees through terror. Likewise, if Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation backfired we’d say he was someone who assembled a tremendous group of advisers and confidantes, but was delusional in thinking he knew how to fight the Civil War. But Lincoln and Sherman got it right and we praise them.

Going back to the Andreesen episode, Marc discusses the 2×2 matrix of “consensus v non-consensus” and “success v failure” and how VCs make their money off of the non-consensus, success businesses. Doesn’t such criteria demand founders to be delusional and selfish? They’re pitching that they have something newer and better than anyone else in the world and that they are deserving of the investor’s money. Doesn’t that fit Ryan’s definition of egotistic? If so, should we rethink what it means to be successful?

In that same episode Marc says he and his team passed on Google because Larry Page and Sergey Brin “were the two most arrogant founders we’d ever met in our lives.” Ryan and Russ might say that Google succeeded in spite of egotism, but this argument loses its salience when it’s also used for Winston Churchill, Steve Jobs, and all the other successful egotists.

I love the sentiment of Ryan’s argument, but I think it fails unless its accompanied by the message that we should reconsider what it means to be successful. In a HBO documentary on Vince Lombardi, the viewer learns of a man who was so obsessed with success on the football field that he cut his honeymoon short to get back to his job and who was largely absent from family life because he wanted to be the best. Is that the success and thriving we should be seeking?

Todd Kreider

Jul 19 2016 at 3:23pm

I doubt ego plays much of a factor in the sophomore slump. First, tastes quickly change and by definition what might have sounded innovative is no longer so two years later.

just as importantly, musicians often put out their first album when they are in their early 20s and the second one two years later. But if you read some liner notes, they spent their teenage years coming up with many of the songs on the album. So many get 5 to 10 years to create the hit debut when songwriting is included but only two years for the second album, which might include only a couple songs left over from the first album, if that.

Callum

Jul 19 2016 at 8:59pm

I love Epictetus and the Stoics. I was just reading Marcus Aurelius the other day. As these are themes which I often think about, I found this podcast to be a useful meditation.

But, lately, EconTalk has had several episodes that you’d be hard pressed to explain their connection to economics, even tangentially. This was one of them.

The episodes that don’t have a clear focus on economics sometimes make me feel like I’m listening to armchair philosophy. That’s something I’m trying to get away from when I listen to EconTalk.

So, +1 for Stoics, -1 for No “EconTalk” = can I get my money back? =)

JRo

Jul 21 2016 at 4:22am

Thank you, gentlemen.

For Russ (and others who spend time in California) I recommend the first 140 pages of Sherman’s memoirs, which includes his ‘Early Recollections of California’ before, during, and after the Gold Rush. It starts with a 198 day (!) journey by sea from New York to Monterey Bay. Imagine that!

Mateo

Jul 21 2016 at 10:00am

Thanks for the episode, because I now know to skip the book.

I cannot tell if someone better defines excess ego than your guest.

Per Kurowski

Jul 21 2016 at 12:06pm

Unless we install in the artificial intelligence of robots the ego that make it hard for these to admit mistakes, they will conquer us and we’re toast!

http://teawithft.blogspot.com/2016/03/artificial-intelligence-has-clear.html

don l rudolph

Jul 23 2016 at 12:56pm

The most insightful words of Jesus are his thoughts

about the ego. “Why can you see the speck of saw dust in your neighbors eye and can’t see the log in your own eye”.” “Judge not lest ye be judged.”

I have to laugh at myself when I swear at the driver in front of me who does not go, even though the light turns green, and then I notice a little old lady in the cross walk. How many judgements come from a place of too little information. This also fits in with Jesus’s tendency toward non-violence. Violence is the height of arrogance for a religious person. Violence says I have a better perspective than God, better knowledge than God, and better judgement than God.

Madeleine

Jul 23 2016 at 5:39pm

Oh man, I REALLY wanted to hear more about the implosion of American Apparel. I was so excited when he brought it up and I listened to the podcast hoping for more gory details… but nope, nothing to be found.

John S Wren

Jul 27 2016 at 1:01pm

[Comment removed pending confirmation of email address. Email the webmaster@econlib.org to request restoring this comment. A valid email address is required to post comments on EconLog and EconTalk.–Econlib Ed.]

Robert Swan

Jul 27 2016 at 7:24pm

Tend to agree with other commenters that Ryan Holiday didn’t seem to walk the walk very convincingly.

I’m wondering whether the book would be better titled Optimism is the Enemy. The discussion didn’t look very much at ego, with more focus on the dangers of high expectations. That still leaves unclear what it is the enemy of. I think it’s happiness as opposed to, e.g., financial success, so maybe the title should be Optimism For Disappointment.

With that I could certainly agree, though I was happy with Alain de Botton’s take on this. Take a look at his Seneca installment of The Consolations of Philosophy. The dog and bicycle are not to be missed! The other episodes are worth watching too, though I’m not so keen on Schopenhauer or Nietzsche.

Then again, ego might be an enemy after all. It’s a dangerous topic. On the one hand, we had Russ and Ryan tut tutting at Churchill’s immense ego. Shortly afterwards they were discussing their strategies for rising above the hoi polloi on Twitter. Churchill might not have called you modest for that, but perhaps he would have said you had much to be modest about.

jw

Jul 28 2016 at 9:48am

Robert Swan,

I understand that this forum is supposed to be more about the exchanging of ideas and less about interactions between commenters, but…

I don’t care what anybody says, that right there was funny!

Thomas D

Jul 31 2016 at 3:53pm

I’m writing this because you couldn’t here me screaming.

Ryan, for someone writing against ego you certainly use the word “I” a lot.

We could argue about the definition of ego but I’ll just through out a few examples.

1. You said it would be boring writing about something you know and it is enjoyable to author a growing experience. I certainly agree, but…, that is pro ego. Others would benefit more if you wrote about something you knew well. Writing to learn is about “I”, i.e., your ego.

2. Theologically, we are supposed to live for others at the expense of our own values. (not my view.)

3. Ego is self-interest. Economically, it is what makes the world go around. All humans benefit in a ego driven society Vs. communism.

4. A healthy ego is “contextual.” Being valuable is “valuable to whom.” If you are a fish expert then people who value fish will value you. If you are an economics professor then those who value economics will value you; and only if they share your principles.

5. Ego maniacs are those who think they are valuable to everyone, ex, Hollywood, sports stars…

Todd Klatt

Aug 3 2016 at 12:56pm

What a lovely interview. I’ve just ordered Mr. Holiday’s book. It feels like it will be relevant companion to How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life and The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which I’m just starting to read.

SaveyourSelf

Aug 16 2016 at 3:10am

Ryan Holiday defined, Ego, as, “not very lovely. Right? It’s selfish; it’s competitive; it’s arrogant; it’s often delusional or unrealistic.”

I define Ego as, “that drive which says YOU must survive.”

He says his concern with, Ego, is, “the way in which ego ceases to be confidence and becomes delusion and selfishness and all these negative things that ultimately are our enemy…”

I didn’t understand everything Ryan Holiday was saying, but I think I got a feel for his core purpose when he said, “I don’t think there’s anything wrong with caring about yourself. I think what happens is when you lose that connection to other people.”

Viewing Ryan’s statements through my personal definition of Ego, I perceived Ryan as saying: ‘it’s okay to think of yourself first, but unacceptable—as in self-defeating—to undervalue others when making decisions and taking action.’ Viewed in this way, he is talking about, Justice. It is fitting, therefore, that he was discussing his ideas on an economics podcast since, Justice, is so foundational to economic models. It was also refreshing and, I thought, appropriate for Mr. Holiday to quote Adam Smith, given Adam Smith had so much to say on the topic of Justice.

I enjoyed the quotes and the biographies all throughout this podcast from both Ryan and Russ. I think my favorite moment was Ryan Holiday’s self-deprecating story about his dinner with the person he admired where he talked ceaselessly and listened not at all. That story will keep me thinking for a long time. It was a nice hour. Thank you for Econtalk.

Comments are closed.