| 0:33 | Intro. [Recording date: November 3, 2016.] Russ Roberts: Today we are talking about his recent book, Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era. Tim, welcome to EconTalk. Thomas Leonard: Thanks, Russ, it's great to be with you. Russ Roberts: Your book is fascinating. A little bit alarming. Way too educational: I learned a little bit too much about the roots of economists' attitudes in the early part of the 20th century and the late part of the 19th. But let's start with the Progressive Era itself. How would you define the Progressive Movement and the Progressive Era? Thomas Leonard: Well, one way to think about it, Russ, is a set, a rather motley set of political and social reform movements that are responding to profoundly changed conditions--economic conditions and social conditions--at the end of the 19th century. Particularly the 1890s. The 1890s were kind of--it's hard to recall in historical retrospect--but a profoundly depressing and difficult era. There was a Great Depression--the worst Depression in U.S. history, with the exception of The Great Depression in the 1930s. There was a double-dip depression, triggered, as is so often the case, by a financial crisis. There was, in addition, profoundly rapid, vertiginous[?], even economic growth going on at the same time. Sounds like a paradox. But despite the rather amazing ups and downs of the economy, over a generation or so--post Civil War--the U.S. economy is quintupling in size--1870--to turn of the century. And with that brought some amazing social changes: Lots of immigration; hopes to work in the factories and the shops and the mines. Urbanization. The rise of the American city. And along with all of that, the rise of the United States as single nation rather than a collection of states. And as, eventually, a global power. So it's a time of enormous change. And we can think about the Progressive Era as a collection of reform movements trying to cope, trying to address and remedy those many and profound changes at the end of the 19th century. Russ Roberts: And part of it involved an increased role for the state--for the government--and a concept, which we still use today: The Administrative State. So, talk about the role that played, as well as the role of expertise--which is, to me an important piece of this story. Thomas Leonard: Right. Well, everybody knows--at least everyone who has read their high school version of American history--that the Progressive Period--and here we can say roughly the first couple of decades of the 20th century--or if you want to be more precise maybe through the end of the First World War, 1918--it is a moment when the State--and particularly the Federal government, importantly the Federal government, not exclusively but for the first time, the Federal Government, takes a much larger role in economic life, especially. But it's not merely the case, as it's sometimes represented, that the Progressives "brought in the State." They certainly enlarged the State; and they, at all levels, particularly with respect to economic relations. But they also changed the nature of the State. So we sometimes read in popular accounts the idea of, you know, the State being big or small--having big government or limited government. But in fact what the Progressives advocated and ultimately succeeded in obtaining, through their activism and through their intellectual persuasion, was what they called the Administration or the Regulatory State. Which was a new beast in American economic and political life. The Administrative State surveils economic life. It investigates economic life, gathering data. It regulates economic life. And it performs all the functions, the Progressives argued, in a kind of scientific way. It's well to remember that a big part of the Progressive Movement was of course about political reform as well as about economic reform. American politics in the Gilded Age was notoriously venal and corrupt and dominated by parties. So, the Progressives not only wanted to expand government--they wanted to change government altogether. So, the Administrative State serves a very interesting and crucial role in the evolution of government economy relations. |

| 6:24 | Russ Roberts: And, that all sounds--I don't happen to agree with it, myself--but that all sounds well-intentioned, and what we would call, today, 'liberal.' Why do you call these reformers, 'illiberal'--meaning, not liberal? What was illiberal about their views and their agenda? Thomas Leonard: Two ways to think about this, Russ. The first is, the term, 'liberal'--it's an old word in English but it's a relatively new word in the political lexicon. So, after the American Civil War, say in the 1870s, if you described a person as liberal, what that meant is the person would be committed to individual freedom and to those institutions that were thought necessary for maintaining individual rights against the State. So, for example, a relatively free-market economy; and laws that protect individual rights against the State. Today we use the term 'classical liberal' to describe that view because the Progressives gave the term, at least in the United States, an entirely different meaning. The Progressives viewed this 19th century classical liberalism as inefficient, as wasteful, as corrupt. And so they certainly were reformers. But they weren't liberals. And in fact what they were trying to do was to dismantle 19th century classical liberalism in the name of health, welfare, and mores. They basically saw individual liberties--which in the American context are sort of very expressly and famously enshrined in the Constitution and Bill of Rights--they thought of those liberties as basically archaic impediments to their reform project of making, you know, the United States healthier and improving welfare and morals, too. So that's the first sense in which they are illiberal--is that there's not a lot of respect for individual rights. Particularly, in the economic context. The second sense, the additional sense in which I'd say the Progressives were illiberal, is, where first--the original sense of the term, Russ. So, when we said someone was 'liberal,' before it became a political term, what we meant is that they were open-minded or tolerant, free from prejudice and bigotry. And as you know, it turns out that a very--a shockingly high percentage of the Progressives, including the progressive economists--were anything but liberal in that traditional sense. They were closed-minded. They were intolerant. And they were bigoted. In fact they-- Russ Roberts: They were racist in ways that even--I'm a fairly cynical person from time to time--and I was shocked by the attitudes of the economists of the day, by Woodrow Wilson--a famous Progressive; Eugene Debs, a famous Socialist. And I'm going to read some quotes later, because saying that they were racist or intolerant doesn't really do justice to their attitudes without quoting their own words, which I will do later. It's kind of shocking. Thomas Leonard: It is shocking. And it shocked me when I first came across these passages piecemeal, working on a related but smaller project many years ago. I sort of was working many years ago on a history of minimum wages, and I saw these absolutely appalling, hateful discussions of workers from Asia or who were immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. African Americans, the disabled. And filed that away, thinking, 'Hmmm. There may be a story here.' And it turns out there is a story. Of the things that's most shocking is not just sort of the hateful views that they had of immigrants and what they called 'defectives,' and African Americans; but the scope of that sort of racism and bigotry. Almost no one, including even white Anglo-Saxon Protestant men, was immune from being characterized as hereditary inferiors. |

| 11:15 | Russ Roberts: And part of this is what is known as eugenics. So, talk about what eugenics are, how it got tangled up with Darwinism, and then filtered through those lenses got into public policy and among economists. Thomas Leonard: Sure. Well, we have to be a little careful, as ever, Russ, because eugenics is and remains today a dirty word--precisely because of the horrors in Central Europe in the middle of the 20th century. But the Progressive Era is roughly a generation before and it had a very different meaning then than it does now. Eugenics, at the time, was the social control of human heredity. And many progressive economists and their reform allies saw eugenics as among the most fundamental of reforms that the state could carry out. In some sense, what's more important than what we would today call the human genome? So, in their view, eugenics, which comes in two flavors--negative eugenics, which is preventing children from the unfit; and positive eugenics, which is promoting more children from the fit--was at the core of any sensible social and economic policy. It's relation to Darwinism is very complicated, Russ, as you know. Each one requires a chapter in the book to sort some of these things out. A Darwinian is someone who looks at outcomes, and, in the jargon of social Darwinism says that those who survive are fittest in some sense. The eugenicist is making the opposite claim. The eugenicist is worried that those who are surviving who are outbreeding their hereditary betters need to be controlled. So, in some sense, though they both are species if you like of evolutionary thought applied to social and economic problems, eugenics starts with a very different premise--which is: The fittest are not surviving. Eugenics judges the races that are fitter ex ante, and that therefore the state must intervene to ensure that that is stopped--that the hereditary inferiors--immigrants, Catholics, and Jews from Southern and Eastern Europe, Asians, African-Americans, and the disabled--not be permitted to perpetuate their kind, or at least not be able to outbreed their biological betters. |

| 14:02 | Russ Roberts: Now, I want to talk about the concept of the state that got promoted at this time. And it's a little bit frightening to me, because it's the exact same discussion that we have today. It's come up many times on this program, and when I critique what turns out--I didn't realize this--to be the progressive attitude, people get very mad at me and write angry things. But I want to quote a little passage here. You say, The progressives developed elaborate, often anthropomorphic depictions of society as an organism.... Henry Carter Adams said the social organism had a "conscious purpose." Political journalist Herbert Croly conceived of the American nation as "an enlarged individual." Ross described society as "a living thing, actuated, like all the higher creatures, by the instinct for self-preservation." The state, Richard T. Ely declared, was "a moral person." These are all very well-respected economists, sociologists of the day. And they saw the state as a distinct thing from the people who made it up. Society, as a distinct thing. And of course government and politics were just the vehicle by which that entity acted, somehow in our interest. This--I call it a 'romance.' It's, I think, a dangerous romance. And many of my listeners--I apologize to you out there--I know you've liked that idea. What I'd like hear from you, Tim, is: Where did that idea come from? It was not in American discourse, I don't think, or other discourse, until then. It seems like it was created around then. Thomas Leonard: Well, it's a really deep question, Russ, in intellectual history. And let me break it down as best I can in short scope in our conversation. Several things are going on at the same time. I will say that you are right to identify this as a very kind of crucial watershed in American intellectual thought. It's a striking intellectual change that happens beginning in the late 19th century, this rejection of the classically liberal tradition which makes the individual prior to the state--the individual, for example, the Social Contract tradition which says that individuals pre-exist the state and they create it for their purposes and presumably can disband it if it doesn't do what those individuals want. The progressives, of course, as you suggest rightly come at it from the other end of the telescope. They think of the state as prior to the individual. And they do use it, as you said in the quote, a very biological and sometimes anthropomorphic characterization of the state. Ely, for one--and by the way, those names may not be familiar to your economist or other listeners--these are the leading lights of American Social Science. Russ Roberts: There's still a prize, I think, named after Ely-- Thomas Leonard: There is. Russ Roberts: The American Economic Association. Thomas Leonard: There are. And if you go to any university where progressives were part of the founding, like Wisconsin or Michigan or Columbia or Wharton, you'll find buildings and programs and prizes named after all these men. And they're not just leaders of the profession, the founders of American social science; they were also influential public intellectuals. Part of the progressive creed, of course, is not merely to hole up in the library and write treatises. They were all public intellectuals. They were all writing op-ed pieces for the newspapers and the religious periodicals. Ely was on the Chautauqua summer lecture circuit--they were public intellectuals as well as leading social scientists. So, back to this idea of the social organism. A bunch of things are going on at the same time. The first is that all of the progressives, all of the leading progressive economists and many of their activist confreres did their graduate work in Germany. In the late 1870s and early 1880s you really couldn't get a Ph.D. in the United States. You had to go to Germany. And they studied at the feet of their historicist German professors, who they greatly admired. And this idea of the state as an organic thing, as a whole distinct from its component parts, and indeed, you know, in some sense superior to its component parts, was partly the product of their graduate training in the kind of German historical school of view. And it also dovetails nicely with evolution as well. Right? If the nation is an organism, it's greater than the sum of the individuals that it comprises. A second influence, Russ, is Darwinism. Darwinism, with its kind of material explanation for evolution, for human evolution, seems to imply that the idea of having inalienable natural rights invested in you by a Creator--the language that you find in the Declaration of Independence--Darwin seems to suggest that's just kind of a nice fiction. A third influence on this crucial change in the way that Americans see the relationship between individuals and the state which we haven't touched on yet is that many of these progressives, and certainly the intellectual leaders among them, were Evangelicals. They grew up in Evangelical homes. They were the sons, and daughters, of ministers and missionaries. And they preached what was known at the time as a Social Gospel. This is a move of American Protestantism away from the idea that the individual must be saved to the idea of a more collective project of redeeming the entire country. Of redeeming America. Which the chapter title of one of my early chapters. And lastly, I would say, fourth, there is a kind of American native discourse of Pragmatism--capital-P Pragmatism--which we associate with John Dewey and others, Charles Pierce [pronounced 'perce'--Econlib Ed.]--which seems to suggest that, you know, just about any departure from previous absolutes is okay provided it proves useful for promoting good things--like welfare and health and higher wages and [?] and all the rest of it. Russ Roberts: Well, I'm always excited when someone other than me mentions Charles Pierce on EconTalk. I think this is the first time. Thomas Leonard: Excellent. Russ Roberts: I've mentioned in the past, I think, that I had a philosophy professor, Richard Smyth, who was a Pierce specialist, and after I studied it at his feet at the U. of North Carolina was able to, years later, talk to him about the relationship between Pierce's and Hayek's ideas, where Hayek was very interested in the evolutionary, practical ideas that proved their worth should be respected even if you didn't understand why they made sense. There's a certain skepticism about the power of human reason in Pierce's work, and in Hayek's, that I'm very fond of. |

| 22:30 | Russ Roberts: But I want to quote another short passage related to this point about the organism. You write, Progressive economists, notably Edwin R. A. Seligman, played a pivotal role in laying the intellectual foundations for the US income tax. Taxes, they said, were not payment for government services. Seligman argued that we pay taxes "simply because the state is a part of us." The taxpayer's duty to the state was no different than the duty to oneself and one's family. By implication, taxes should vary with ability to pay. And I think that attitude, again, is still very common among many Americans today, and elsewhere around the world--that somehow, supporting the state is just like supporting yourself: this idea that we, through the state do things; there are things the state does that benefits us. And I find that difficult, because in fact, almost everything the state does benefits some of us and hurts some of us. And I feel that many people take advantage of that romance to push things for their own self-interest, claiming they are good for all of us when in fact they are good for them and not for the rest of us. So, I was just very struck by how common that attitude was then. Thomas Leonard: Well, it's a great example, Russ, of the sort of organicist view of the state put into concrete economic action. When the Constitution was amended in 1913 to pass the income tax, economists were absolutely--today we'd call them 'public finance economists'--were at the forefront of that movement to move the United States government away from funding itself with tariff revenues and with taxes on tobacco and alcohol. And to, instead, tax income. It is a watershed moment, because if you are going to have an administrative state, it needs to be funded. And an income tax is a much better, much more reliable way of funding a large institution of the sort that the progressives imagined when they were drawing up the blueprints for the administrative state. Russ Roberts: Well, I'm going to quote Irving Fisher, who I used to like until I read your book. I used to think Irving Fisher was just--I mean, he's a wonderful writer; he had a lot of good ideas about interest rates and their relationship to inflation which I found useful thinking about these things. He wrote--again, early part of the 20th century and famously lost money during the Great Depression, unprepared for that event; always entertaining for non-economists to point those things out. But, his social attitudes were rather unpleasant. Again, a quote from the book: ... social science experts gave elitism a new form and rationale in the Progressive Era, one expanded on by Irving Fisher. The United States had abandoned laissez-faire, Fisher said, out of recognition that "the world consisted of two classes--the educated and the ignorant--and it is essential for progress that the former should be allowed to dominate the latter." And that--there are many other things Fisher said that were worse than that. But I wanted to use that example--I mean, it's a perfect example of the justification for why experts should be in charge to run other people's lives. And I want to ask you: that attitude of course remains today in many forms among economists and others in power. How much do you attribute simply to the economists' desire to have more power? So, there are many, many quotes in the book from economists justifying an expanded role for the state. But it's an expanded role for themselves. So, it's a kind of awkward form of public intellectualism. And it remains so to me to this day. Thomas Leonard: I think that's well-put, Russ. Sometimes if you step back from the scholarly trees and look at the whole forest, one of the things that's most shocking, or at least striking a hundred years on, is that in proposing to fundamentally change the U.S. state and its politics and to fundamentally remake its economic life, the progressive economists--and their reform allies, in other institutions; it's not just a bunch of academics; it's also progressives who are working in settlement houses and who are investigatory journalists or who are working in other community groups, or in government--their best idea for spearheading all those reforms is, 'Well, why don't we install me and my friends?' To put it baldly. And, it is this--I don't think progressives today are quite as egregious, because, you know, experience has taught that this kind of heroic view of expertise, simultaneous heroic and self-serving, is sometimes misplaced. There is this very quintessentially American combination of naivete on the one hand--you know, Fisher was brilliant, but the economists really didn't know what they claimed to know in arguing that they should be running an administrative state. Russ Roberts: Huh. Thomas Leonard: And it was also incredibly arrogant, at the same time. Right? Naive and arrogant. Russ Roberts: I don't think things have changed at all. I'm serious. I'm not trying to be cute here. Thomas Leonard: Yup. Russ Roberts: I think the general thrust of welfare economics--which means something very specific in economic theory; it's not the study of payments to poor people: it's the study of wellbeing, human wellbeing--I find depressingly narrow, for starters. Overly confident. And I think incredibly self-serving: to place us as the engineers of the betterment of those who don't understand the world as well as we do, is the claim. And I find it depressing. Thomas Leonard: Well, there's essentially a moment, Russ, that happens at the end of the First World War. And it's a very awkward moment for the Progressives, and for the progressive economists in particular. And it's this: That the economics that they'd been preaching since their graduate school days, for a generation, was a German-style economics. One modified to American conditions, but German in spirit. And so, two[too?], was their model of the administrative state: how economic policy would be put into practice, and so, too, the idea of the expert economist as the keystone, the key figure in the administrative state. All of these ideas, they borrowed from Germany. And of course Germany became a dirty word in American discourse at all levels during WWI. Even beer was vilified for its German connections. So, having a German economics and a German view of expertise; and the Germans, Germany as the model for the world in designing a scientific, rational, expert administrative state was politically completely untenable. But what happened--and you can see this in Fisher's Presidential Address, just a month or so after hostilities have ended. His Presidential Address to the AEA (American Economic Association) meetings, 'Economists in the Service of the State,' he says 'Yes, well, we were wrong about Germany, but we're not wrong about the administrative state. We're not wrong about the necessity of having the experts in charge.' What did change, I think--one important change that takes place after the [?] period in the 1920s--economics becomes a little more technocratic: So we evolve towards the view where experts given a goal, a set of goals by some political process, and then decide the best route to get to that goal. Which is a bit different from the more heroic Progressive Era concept, which is experts not only tell you how to get from A to B, they tell you what your goals should be in the first place. Like preachers. |

| 31:54 | Russ Roberts: So, I can't help--this is not in your book, but I can't help but remark--and I am going to defend the Progressives now, which is not easy for me, but I'm going to make a go. So, there is this disillusionment or a little bit of soul-searching after WWI, because Germany was blamed, correctly or not, for the conflict. And of course Germany--it's always important to remember that Germany, this militaristic, authoritarian state, was the first state to have serious welfare, traditional welfare activity such as social security-- Thomas Leonard: That's right-- Russ Roberts: And other things. So, okay. So, they realized--oops, we've got to get rid of part--we have to concede that part of this was tainted. Then, of course, WWII and the Holocaust ends any use of eugenics and race-based thinking among liberals, for the next 75 years. And, can't one argue that, 'Okay, so progressivism has these hideous, racist'--and I'm going to give you some more quotes in a little bit; we're not exaggerating here--hideous racist origins. 'They had an intolerant and horrible set of attitudes toward women, certain nationalities, Jews, certain, again, races; and yet they also had their good stuff. So, okay, they had some bad ideas. They get rid of those and now they just have the good part.' What do you say to that? And more importantly, why should we care? I mean, this is a fascinating book, but, okay, so modern progressives have bad ancestors. Is that a big deal? Thomas Leonard: I have to say, Russ, I'm always skeptical of the argument, 'This time it's different.' As you know from reading the book, one of the main arguments argued in support of minimum wages during the 'teens, a campaign led by progressive activists and progressive economists, was that if you fixed what we today call a binding minimum wage, you would disemploy idle, inferior workers. The idea was that productivity, we'd say today, was connected with some metric of biological inferiority. So if you set a minimum wage high enough you'd make sure that the Jews and Catholics and Orthodox Christians from Southern and Eastern Europe were kept out; that the Asians, who were vilified as coolies were kept out; and those parasites already in the labor force who couldn't be productive enough to justify a properly-set minimum would be idled and could be dealt with appropriately. So that's an example of the way that progressives harnessed eugenic thinking in defense of something as anodyne as a minimum wage. The idea it was not merely raising wages but it was also performing this incredibly important and valuable eugenic social service. Russ Roberts: 'But now no one puts forward a minimum wage now as a racist. They are just trying to help poor people.' Thomas Leonard: Well, that's certainly how the rhetoric goes. There's two parts to this. If we were giving the textbook version, Russ, we'd talk about the scientific or positive claims; and then the normative claims. What's interesting in retrospect is that the original progressives, unlike their namesakes today, saw potential job loss as a feature, not as a bug, right? Whereas today it's the other way around: Folks who are honest about, say, a $15 minimum will acknowledge that, at least at that level we start to lose jobs and/or hours. And the irony, of course, is we see this, if we see it correctly today, as a cost of minimum wage set too high rather than a benefit, which is how the original progressives saw it. And I must say: I'm very sympathetic to your position at least as you sketched it. It's entirely possible to be a proponent of the minimum wage in the 21st century without subscribing to the hateful views of your namesake's ancestors. That's quite right. But I think what we need to do, though, is to step back from the sensational aspects of eugenics and racism and look at the very idea of an administrative state and expertise in the first place. So, I quite agree that 21st century progressives, those who call themselves progressive in the American political context today, do not, and thank goodness, share the views of their intellectual namesakes. And that's all for the good. But I do think, though, that a couple of notions--and we're not talking here about racism or eugenics--have carried over from a century ago. And here's what they are. One we've touched on, and that's this idea that, I think if you really sat down over a glass of wine with a thoughtful progressive, you'd find that they still hold to progressivism's core faith, is that: If smart, well-intended people are put in charge, the best and the brightest, then progress--economic progress, social progress--will inevitably follow. I think that attitude is not nearly as arrogant or heroic necessarily, but that fundamental faith remains. And the second thing I think that remains connecting 21st century progressives to their namesakes of a century ago is this idea the free markets are intrinsically--intrinsically, not in practice but in their very design, their nature--unjust and wasteful. And that means that free markets require--goes the argument--the visible hand of a vigorous, activist state that's empowered to investigate and regulate. Russ Roberts: Yeah, and I think you're right. And nowhere in the book do you claim that there's something wrong with being in favor of the minimum wage today because it has racist roots or whatever. That's not the theme of your book at all. And I think you're exactly right that what has remained which sounds benign, I find dangerous. Which is this idea that certain people know better about how to live or how other people should live. We certainly see that in the Behavioral Economics sphere to some extent, and we see it elsewhere. |

| 39:19 | Russ Roberts: I want to come back to the minimum wage. I'm going to talk about that in some length, and not just the minimum wage but the labor force and how policy should be toward it. But I don't want to miss a chance to discuss Woodrow Wilson for a minute. And then we'll use him as our segue to the minimum wage. Woodrow Wilson--I thought the U.S. intervention in WWI earlier on was a terrible mistake. And certainly the Versailles Treaty which Wilson championed and influenced, it appears, was also a terrible mistake. But my perception of Wilson was--he had been a professor at Princeton, and he was an idealist. That's my view of him, until I read your book--which is: 'The road to hell is paved with good intentions; he meant well; he tried to do well; and in entering WWI he tried to do well, and in emphasizing self-determination, and the Versailles Treaty's different components.' But I get a different perspective on him after reading your book. And here's a quote from the book: "Professor Woodrow Wilson"--this is before he was President; he was at Princeton, I assume-- Professor Woodrow Wilson told his Atlantic Monthly readers that the freed slaves and their descendants were unprepared for freedom. The freedmen were "unpracticed in liberty, unschooled in self control, never sobered by the discipline of self support, never established in any habit of prudence... insolent and aggressive, sick of work, [and] covetous of pleasure." Jim Crow was needed, Wilson said, because without it, black Americans "were a danger to themselves as well as to those whom they had once served." When President Wilson arrived in Washington, his administration resegregated the federal government, hounding from office large numbers of black federal employees. It's fascinating to me that this aspect of Wilson, which is absolutely horrific, is not widely known. I don't think it is. America I wrong? And why isn't it widely known, if I'm right? Thomas Leonard: Well, it's known among scholars, Russ, but I don't think it's widely known among the public. It is true. You may know that there was a controversy here--I'm sitting in Princeton University--there was a kerfuffle last year when some student activists occupied the President's office and made a set of demands for change. One of those was that Wilson's name be removed from the School of Public and International Affairs, which is where I'm sitting right now. And that his name also be removed from Wilson College, which is one of the residential colleges here, because he was a racist. And, Princeton is a university, so it responded by convening a committee of scholars, and it's elicited opinions from various scholars outside the university; and made a decision. And the upshot is nothing is happening, though they are going to, perhaps as a token, take down a mural of Woodrow Wilson in Wilson College. But the name will remain. Russ Roberts: Maybe people think it's the sporting goods company. You know, if they take down the mural. Thomas Leonard: Maybe so. He is, in fact, holding a baseball, throwing out the opening day pitch. So, I have to say, you know, part of me was proud of those students, in a sense that they had learned some of their history and they knew that Wilson's past, his record on racism as a defender of Jim Crow--and Jim Crow in this context means effectively annulling the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments . He advocated that. But I would want to--I would have gone further. And that's what this passage is so important about, Russ. It's not merely the fact that Wilson was a racist. Lots of people had race prejudice at that time. That was widespread. I think what we want to draw--it's helpful. History helps us to draw distinction between people who had arguably unpleasant views--and racism is certainly unpleasant--and those who acted upon those views in a way that harmed others. And third, those who acted upon those views using the coercive power of the state to harm others. Remember--you know, Wilson is elected in 1912. Okay? This is more--this is 50 years later after Appomattox. The Federal workforce is--the beating economic heart of the black bourgeoisie in Washington, D.C. It's a source of pride. It's a source of income. It's a source of social standing. It's the only place in America where a black man can give orders to a white man and have them carried out without any sort of retaliation or violence. And Wilson--who won the election mostly by accident, let's remember--he won the election because Teddy Roosevelt ran as a Progressive, capital "P"-Progressive, splitting the Republican vote--Wilson got majorities, popular majorities, only in the states of the Confederacy. And his henchmen, McAdoo and others proceeded to desegregate--or rather to resegregate--the federal workforce. It was a devastating blow. That's not just racism. That's racism acted upon. That's racism enacted using the coercive power of the state. Which is most sinister of all. |

| 45:32 | Russ Roberts: So, I'm going to read another long passage. I apologize to listeners who don't like to be read to. If all goes as planned, I interviewed Doug Lemov in last week's episode. So we talked about reading out loud to folks. So, I notice some people don't like it. But I want to read this passage because I think it is a great example of what we've been talking about. And I think some listeners might think I've been exaggerating about the attitudes of the day among economists and leading social scientists. And this will lead us into a conversation of what you call 'the menace of the unemployable'--this idea that immigrants and non-Anglo Saxon, non-white workers were bad for the country. And it has a lot of echoes of today's world where we're talking about how to deal with the fact that some workers may not be employable, may be put out of work by technology. So, this is, again, a very long excerpt; but I think it's important and I want to give people a flavor of the book; and then we'll talk about it. Thomas Leonard: Let's hear it. Russ Roberts: Yeah, I know as an author, when people say, 'Do you mind if I read you a passage from your book?' Music to my ears. Thomas Leonard: Yeah. Russ Roberts: Here we go: The term "unemployable," popularized by Sydney and Beatrice Webb, was a misnomer, for many of the unemployable were in fact employed and others desperately wanted to be. The Webbs used the term to describe people incapable of work, as well as those who could work but who accepted wages below a standard reformers judged acceptable. The latter group posed the threat.

University of Chicago Sociologist Charles Henderson put it plainly: the unemployable were those who "bid low against competent and self-supporting men who were trying to maintain or raise their standard of living. And they can do this just because they are irresponsible and partly parasitic." By "parasite," Henderson meant that the unemployable worker earned less than was required to support him- or herself, creating a shortfall that had to be met by other members of the worker's household or by private or public charity.

Henderson borrowed "parasite" from Sydney and Beatrice Webb's Industrial Democracy, which was influential among American labor reformers. The Webbs affixed the term to sweatshop industries that paid wages below a living wage, and to the workers who accepted these wages....

... Since "parasites," by assumption, could not pay their own way, their economic competition served only to drag down the wages of their betters. Letting the unemployable work was thus socially destructive, so, went the argument, they should be removed from the workforce, kept at home, segregated in rural labor colonies, or placed in institutions. And you go on to write, and I'm going to now indict, with your words, Woodrow Wilson again and Richard Ely, prominent economists of the day: The low-standard or undercutting-of-wages part of the theory, got its start with the violent activism of white Americans against Chinese immigrant workers. The title of a pamphlet published by the American Federation of Labor trenchantly captured the heart of the claim: Meat versus Rice: American Manhood against Asiatic Coolieism, Which Shall Survive? If wages were determined by living standards rather than by productivity, then the meat-eating Anglo-Saxon could not compete with the Chinese worker accustomed to eating rice.

Professor Woodrow Wilson, in his popular History of the American People, preferred the same theory of low-standard races undercutting American wages, adding a fillip of racism to cement the notion that race explained the low standards. White laborers, unable to "live upon a handful of rice for a pittance," could not compete with the Chinese, "who with their yellow skin and strange debasing habits of life seemed to them hardly fellow men at all but evil spirits, rather." And now I'm going to quote where you talk about Richard Ely, and this is so depressing: The fullest unfolding of our national faculties, Ely asserted, required the "exclusion of discordant elements--like, for example, the Chinese." Ely assumed that a unified American nation required racial homogeneity. As for South Asians, Ely proposed that famine-relief efforts in India should be suspended. Why not, Ely ventured, "let the famine continue for the sake of race improvement?" And the quote goes on to talk about anti-Semitism, from John Commons--is it John Commons, is that correct? Thomas Leonard: John R. Commons. Russ Roberts: Who was--who was John R. Commons? Thomas Leonard: John R. Commons was the leading labor historian and economist of the day. There's a building named for him still at Wisconsin. He was a colleague of Richard T. Ely's and Edward A. Ross's, founders of Wisconsin Social Science and also key leaders in what's known as the Wisconsin idea--the sort of prototype of the administrative state, first built in Wisconsin. |

| 50:40 | Russ Roberts: So, this idea, that certain races, nationalities, etc., would drag down the wages of native-born Americans, is tragically still in our discourse today. But in its day, in the Progressive Era, this idea that somehow a Chinese worker, because of his desire for rice, would be willing to work for a lower wage than a meat-eating Anglo-Saxon--I can't tell you how disturbing that idea is to me. And again, I'm not naive--like you said, we understand that people of that era didn't have the same attitudes we have. But to use that as a justification for keeping them out of the workforce is so sad. Thomas Leonard: Yeah. Viewed from today, it's pretty ugly stuff, Russ. Some of these passages that you've read aloud were hard for me to write. But for the most part, these quotes are, if you like, letting the men who said them hang themselves. It doesn't require any further sorts of indictment than to see what sorts of arguments that they made. One thing that--it turns that the Chinese play a really key role in the American anti-immigration movement. The Chinese were the first race--using the terminology of the day--to be legally excluded from the United States on racial grounds because they were Chinese. The Chinese Exclusion Act dates to 1882, and it follows a decade or more of [?] mob violence against Chinese immigrants and Chinese workers in California. And if you think about it, it's ugly of course, but it's also a little bit odd. Because the Chinese worker who they are vilifying as coolies--that's a very important and particular usage--the Chinese worker is basically being accused of being hard-working, of being law-abiding, of being frugal and resourceful. And these are quintessentially American virtues, aren't they? At least in the small-'r' republican tradition. So, if you are going to try to demonize someone as a threat, as a hereditary threat, as a political threat, and of course as an economic threat to Anglo-Saxon American workers, you have to come up with someone else. And so, what they came up with--the progressives, activists, the economists, and some of the labor unions--was that they had this sort of supernatural ability to subsist on nothing. And that was in fact linked to their race. Today we might give it a cultural explanation, but at the time it was deemed an innate quality. And furthermore, that living standard, this ability to live at subsistence, was not only determined by race but it also somehow led them to accept unusually substandard low wages. Of course, that doesn't follow at all if you think about it. Just because you live frugally doesn't mean that you are willing to accept low wages. If there's any competition in the market, you won't. It just means you are saving your money so that maybe you can bring some more of your family to safety, or maybe start a small business. So the actual economics of it are a little bit puzzling. And we could talk about that if you want, but I don't want to get too far in the weeds. This is the moment where Labor Economics, which it was not yet called--that's anachronistic--still hadn't fully adopted marginal productivity as a theory of how wages are determined. It's sort of a mishmash, say: there's still an idea that wages are partly determined by living standards and if you can say that living standard is a function of race or indeed of gender, then you are off to the races. And, just to finish the thought, Russ, this model of demonizing the Chinese as under-living--that was sort of the term of the art; that's what made them a threat--was later adapted and applied to immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, and so-called defectives--people with physical and mental disabilities. And ultimately to women, too, using the same sort of argument. Russ Roberts: Just the parallel where today people say that 'We need a minimum wage because people can't live on the wages they are earning'--I'm always--that phrase always strikes me as bizarre. I mean, everybody would like to earn more. And certainly many of us would like to see poorer people earn more. But the idea that they are not living somehow because they foolishly accepted these wages and we should effectively stop this legal transaction, make it illegal, by a minimum wage. And then, when you ask people, 'Well, what if there are people who are going to be put out of work?', first they argue, 'Well, they probably won't be. But if they are, that's why we need, say, universal basic income, or expanded welfare state.' And this steering of--there's no possibility of people climbing the ladder, no possibility of people getting work experience to improve themselves, no recognition of the importance of work for human wellbeing and a sense of pride and dignity--again, I feel like a lot of what we hear today in the debate is--it's the same argument, just not quite as racist. Thomas Leonard: That's right. I think that's exactly right. And I should say that this notion that these various inferior peoples, races and genders and the disabled are wrongfully usurping the jobs that rightly belong to white, male Anglo-Saxon workers, has a second component, too. That's where the term 'Race Suicide' comes from. The fear--and this is where eugenics adds meat to the argument--it's not just, 'It's unfair economic competition.' The idea is that the American working man will not lower his standard to the coolie level, and will instead have fewer children. And because of that, the inferior, the hereditary inferiors, will outbreed their biological betters. That's what Race Suicide means. That's what Edward A. Ross named the process. And the idea-- Russ Roberts: He was a Sociologist, correct? Or was he an Economist? Thomas Leonard: He was a Sociologist, and probably the most prominent intellectual among Sociologists of the day. If you'd asked an American, 'Name a Sociologist,' they probably would have named Ross, a pioneer in the field. And 'Race Suicide' is what President Theodore Roosevelt called the greatest problem of civilization. It's not just a bunch of academics discoursing on theories of wage determination. This was viewed by Roosevelt and many other progressives as a profoundly important economic problem. And, you know, I think, one of the things we might want to say, Russ, since I see we're running out of time, is that the original progressives--and this I hope will connect with your last point--were deeply ambivalent about the poor. It's really, I say in the book, the Great Contradiction at the heart of the Progressive Era reform movement. I think they felt genuine compassion for "the people," right? Which is to say those groups they judged worthy of American citizenship and employment. And they were offered the helping hand, the deserving poor, of state uplift. But simultaneously, they scorned millions of ordinary people who happened to be disabled or belonging to a "inferior race," or female. And they were offered the closed hand of exclusion. And I think that's what connects to today's discourse. There's still--you kind of can't believe it, but if you haven't been living under a rock for the past few months, there is still a view at large that certain classes--indeed, entire races--are not worthy of American citizenship, much less employment. |

| 59:39 | Russ Roberts: I'm glad you mentioned that, because I wanted to make it clear that although I've been critical of progressives' views towards, say, minimum wage or other issues, it's now the case that the Right in America has taken up a big chunk of the kind of argument progressives were making, and making the same kind of arguments--just not from the Left, from the Right--about the need to keep America pure. An implicit form of eugenic thinking without the worst pieces of it. But not really that much different in its intellectual roots. Thomas Leonard: That's quite right. The kind of right-wing populism you are hearing from, the Trump campaign, is just eerily similar to the arguments that were sketched in my book of a period a hundred years ago. When I set out to write this book, it never occurred to me that these sort of ugly sentiments would again become an important part of our national political discourse. But here they are again. Russ Roberts: Yeah. The Race Suicide idea is really rampant among the American Right today--this idea that America needs to be white, or pure, or somehow our national destiny is going to be contaminated by immigrants of certain kinds because they are not capable of becoming part of a democracy, part of the workforce, whatever it is. And again, those attitudes are all over your book, which were common in the 1880s, 1890s, 1910, and about immigrants whether they were from Eastern Europe as Jews, the Chinese, Italians, Irish, or African-Americans. It's just very depressing. Thomas Leonard: And I would also say, Russ, something we really want to avoid doing, in retrospect, looking backward a century, is: We want to make sure we don't make the tempting mistake of condemning all that's eugenics and race science as pseudoscience. That would be our view of it, today. But at the time, it was nothing of the sort. It was the best science of the day. And Progressivism is nothing if not scientific in the way it conceives of the relationship of the expert to the administrative state and the relationship of the administrative state to the economy. It's really hard to appreciate in retrospect. But these people were not cranks. They were not proto-fascists or any such thing. They were the leading lights, intellectually and politically of their time. And they thought they had it right. They thought that they were simply taking the best science of the day and applying to important economic and social problems. I think, if nothing else, it should counsel humility for economists and others who do policy today. |

| 1:02:38 | Russ Roberts: Let's close with going back to this Richard Ely quote--I always pronounced it e-lai, but it's evidently e-lee. Is that correct? Thomas Leonard: Mmm-hmmm. Yeah, I think so. Russ Roberts: That famine efforts in India should be suspended because "let the famine continue for the sake of race improvement". I've always been proud of the role economists played in the slavery argument, in England and in the United States. So, we go back to John Stuart Mill and Adam Smith and others. And we have a wonderful essay here at the Library of Economics and Liberty by David Levy and Sandra Peart on the origins of racism. And the slavery movement, the justifications for slavery ties in to a recent episode we had with Mike Munger on this issue. Thomas Leonard: Fantastic work. Fantastic. Russ Roberts: But in some ways--thanks. Not my work. But yeah. But in some ways it's sort of the predecessor of the Progressive philosophy, this idea that the betters need to take care of the inferiors. Or at least keep them away, if you can't help them. And I think about how Mill and Smith saw--had so much respect for the dignity of human beings, regardless of their race, regardless of their nationality: that Smith was disdainful of people who said that the Irish couldn't take care of themselves. Or that all kinds of people deserved respect as individuals. And we went, somehow from that attitude to the attitudes you talk about in the book--Richard Ely, who would say, it's better to let people in India die because they are racial inferiors. How did that come to pass? I know that's a--that's a tough question to end with, on one foot, so to speak. But you have any thoughts on that? It's very sad to me. Thomas Leonard: Well, I think that--there obviously is a connection to the, you know, mid-19th century abolitionist movement, the anti-slavery movement. And I guess, one caution I would make is that, I'm happy to claim Smith and Mill as economists. But the idea of an economist as a vocation--as a job, as a profession, is something that really only emerges in the late 19th, early 20th century. So, people who wrote brilliantly about economic matters, like Smith and like Mill, I'm happy to claim them, but you know, Mill was a civil servant; and Smith was a professor of moral philosophy. And you know, Marx was an agitator and a journalist. And all the economists that we read in a History of Economic Thought course were not professionals until this moment. That's an important part, actually, in the United States, of what the Progressives did, is they professionalized economics. They made it academic and they made it expert. And, so, I wouldn't want to claim that there's some sort of, you know, incredible phase change that happens. I would make one important point, though, I think, in trying to respond to the question. And that's this, is that: One thing about eugenics, about using the state to improve human heredity, is: You can't do it without a regulatory state, really. In any meaningful way. That's not to say that today, in the era[aura?] of genetic testing and screening, there isn't a form of eugenics going on. There is. The difference, though, is: Who gets to decide who is fittest? Is it parents in consultation with their doctors? Or as it was a hundred years ago, is it the state as being directed by experts? So, at least in terms of the Progressive Era, there's no eugenics without the advent of the administrative state. Of course there's eugenic ideas. There's a few places--if you like, the Oneida Community, where it's being practiced. But you do need, if you are going to do a serious wholesale revision of human heredity in the name of improving it, you need a powerful state to carry that out. So, actual eugenic policy, as opposed to eugenic thought, had to await the arrival of an administrative state with the power to carry it out. |

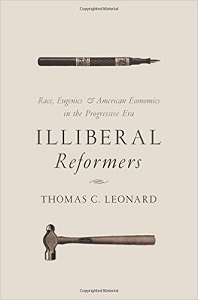

Were the first professional economists racists? Thomas Leonard of Princeton University and author of Illiberal Reformers talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about his book--a portrait of the progressive movement and its early advocates at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. The economists of that time were eager to champion the power of the state and its ability to regulate capitalism successfully. Leonard exposes the racist origins of these ideas and the role eugenics played in the early days of professional economics. Woodrow Wilson takes a beating as well.

Were the first professional economists racists? Thomas Leonard of Princeton University and author of Illiberal Reformers talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about his book--a portrait of the progressive movement and its early advocates at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. The economists of that time were eager to champion the power of the state and its ability to regulate capitalism successfully. Leonard exposes the racist origins of these ideas and the role eugenics played in the early days of professional economics. Woodrow Wilson takes a beating as well.

READER COMMENTS

Greg G

Dec 5 2016 at 10:45am

Thanks to both guest and host for a superb podcast. Every political movement tends to romanticize and sanitize its history and progressivism is certainly guilty of that.

It’s worth remembering though that pervasive racism and a casual acceptance of Eugenics wasn’t the thing that separated the American progressives of this era from conservatives. It was the thing that united them.

They fought bitterly over economic issues but racial prejudice and Eugenics, not so much. Carrie Buck lost the most famous Supreme Court Eugenics case 8-1. The tone of that decision indicated that almost everyone understood that common sense dictated the decision.

It was eventually understood that Social Darwinists had their Darwinism exactly backwards. Selection is reliable and relentless. If nature needs help, it is with variation. It is lack of genetic diversity that causes species to go extinct. Nature can’t select for a needed trait that isn’t there. There is no one genetic type that succeeds best in all possible environments. Genetically diverse populations are the most evolutionarily robust. Genetically similar populations are evolutionarily fragile.

It was only later that Eugenics went out of style. First, the Nazis showed the horrific lengths that such logic can be taken to. Next, it was discovered that Carrie Buck wasn’t even feeble minded. This cast much needed doubt on the trustworthiness of bureaucrats to make such decisions.

And just in case anybody thinks that the cautionary tale here ends with warnings about too much government power, let’s remember the biggest terrorist movement of the Progressive Era was anarchism.

Phil S

Dec 5 2016 at 10:46am

A thought-provoking podcast.

Roberts and Leonard draw parallels between historical and contemporary positions on issues such as the minimum wage. Although my own sensibilities can probably be best described as “classical liberal”, I am wary of using interpretations of the history of ideas to argue contemporary politics.

First, although there is no doubt that some of these progressive intellectuals were racist, they should be judged against the background of their time. The quotations mentioned are shocking to our modern ears, but it is easy to find equally shocking statements from across the political spectrum. Denouncing these people as particularly racist requires a more thorough examination of historical context than just a few quotations, if any denouncing is appropriate at all.

Second, I am skeptical of intellectual constructions that argue that some historical ideas necessarily lead to certain outcomes one disagrees with. For example, in most of Western Europe unlike in the United States, the conservative intellectual tradition is favorable to a strong state. Ideas that Americans would call communitarian are strongly intertwined with nationalism in Europe, putting the “national community” above the individual. Read conservative European philosophers of ideas or historians, and you will find accounts, just as persuasive as Leonard’s, that “progressive” ideas are the necessary consequence of economic liberalism run amok, and that all the ills of the modern world go back to 19th century classical liberals substituting the markets and individual whims for political will.

Historical context is interesting and important to study, but I think in reality things are much muddled, people are willing to hold contradictory and to some extent incoherent views. Simply exhibiting some logical chain of argument leading from a historically significant thinker to some idea does not tell us much about either the value of the idea today, or how people today arrived at that idea and why they embraced it.

Madeleine

Dec 5 2016 at 6:26pm

THANK YOU so much for your distinction between Darwinism and Eugenics, Professor Leonard. They are indeed the opposite: Darwinism is “survival of the fittest”, Eugenics is “picking winners and losers because so-and-so thinks they have a better idea of what is fittest.”

Also, Professor Leonard is correct to point out that these men were going off of the top science of the day, not fringe cranks, and that this should make us all more cautious.

Unfortunately, I think there still is a lot of racist and sexist pseudoscience floating around. It might not be as obvious as stuff like eugenics, telegony, and phrenology, but like they say: hindsight is 20/20.

Nonlin_org

Dec 5 2016 at 6:46pm

I don’t see any conflict between Darwinism and eugenics. Both assume the struggle between the weak and the strong with the strong eliminating the weak – it’s pure Nazism and pure Stalinism. Here is your confused quote:

“A Darwinian is someone who looks at outcomes, and, in the jargon of social Darwinism says that those who survive are fittest in some sense. The eugenicist is making the opposite claim. The eugenicist is worried that those who are surviving who are outbreeding their hereditary betters need to be controlled”.

Care to explain?

In fact, Darwinism never made any sense whatsoever. It’s time to retire:

a. “Natural” in natural selection – everything is natural

b. “Unguided” as in unguided natural selection – all known selection is guided and “unguided” is just unknowable

c. “Fit” as in survival of the fittest – we cannot measure “fit” except as “survival”

d. “Arising” as in Arising of Everything and Life vs. Entropy

e. Recognize that Selection and Survival are one and the same – the selected survive and the surviving have been selected

f. “Randomness” as in random mutations

g. “Natura non facit saltum” (gradualism) is contrary to Quantum Mechanics as well as contrary to sexual reproduction

h. “Benefit” and “optimization” – these are anthropic concepts that make no sense in a mechanistic universe.

Nonlin_org

Dec 5 2016 at 6:56pm

Somewhere towards the end you both agree that the current U.S. right is racist.

That was totally out of the blue and without any support. I cannot believe you’re falling pray to the leftist propaganda machine. It seems the American people outfoxed you on this one.

Of course there will be individual racists on both sides but to generalize from there it’s ludicrous.

The most egregious racism – if you ask me – it’s happening in Detroit and Baltimore and Chicago where the likes of Clinton keep the people impoverished while milking them for votes once every two or four years.

Greg G

Dec 5 2016 at 7:34pm

Nonlin,

You say that you don’t see the conflict between Darwinism and eugenics. And you have proven that you don’t see it.

First of all, go ahead and dispense with the “natural” in natural selection. Darwinism certainly does not depend on distinguishing natural from unnatural. It works just as well if we regard everything as natural. You are right about that.

Variation and selection are the two key concepts in Darwinism. It doesn’t even matter what causes the variation. As long as you have variation, the different varieties will survive in unequal numbers and that will drive evolution.

To say that mutations are “random” is just another way of saying we don’t know much about what causes them. Some people like to think this makes room for God to direct the mutations. Others think this just substitutes two things we don’t understand for one thing we don’t understand. Either way, whatever causes variation will result in evolution.

Fitness is measured as successful reproduction, not mere survival. An organism with a long life but no descendants is an evolutionary dead end.

Selection is not random. What is selected for is reproductive success in the existing environment. The environment is specific, not random. This has a ratcheting effect of tailoring successive generations of organisms for specific environments.

Eugenics is in conflict with Darwinism because it assumes that, without human intervention, evolution is in danger of selecting for the organisms least adapted to the current environment. There is no such danger for Darwinists.

But the current environment may not be the future environment. That is why genetic diversity makes populations evolutionarily robust and genetic similarity makes populations evolutionarily fragile. Eugenicists were attempting to make populations more genetically similar.

Bob

Dec 5 2016 at 9:53pm

I support voluntary eugenics. That’s part of why I’m not having kids. You’re all welcome, BTW. 🙂

It’s interesting to think about demographics and incentives. I suspect most people on this page are economically-minded or at least economically-interested. Would it be shocking if the average intelligence of people on welfare was lower than MIT graduates, for example? Probably not. In fact it wouldn’t really be that shocking if we looked at aggregate measures of people on welfare vs. not and the welfare pool was at least slightly less well off on many measures, including average intelligence, compared to the not-on-welfare pool. I’m not making any moral judgement about this, just describing possible demographic realities about people on welfare vs. not.

If this is so, there’s a certain sense in which welfare programs, especially involuntarily funded ones which permit long-term dependency, or function to subsidize bad choices (having kids you can’t afford or lack the skill to raise well) might well be dysgenic. If true, wouldn’t that mean various federal welfare programs are form of eugenics in reverse (i.e. dysgenics)?

One might also think about how family-planning education and services (birth control, abortion) might also have a dysgenic effect because family-planning is most prevalent among the better educated. It’s common knowledge that number of children per family has an inverse relationship to education level.

If true, that would mean current-day progressives who favor government efforts on family-planning (ACA birth control policy, funding Planned Parenthood, etc) and also favor a larger welfare state, are still advocating a kind of eugenics (actually dysgenics). Though surely not on purpose — just as a side effect of well-intentioned policies to help people in need.

What do you think? Are family-planning, welfare dependency, and subsidies for single mothers likely to have a dysgenic effect? Are current-day progressives still advocating eugenics (though on accident this time)?

Ian

Dec 5 2016 at 11:37pm

There’s a sense in which every government action or inaction is de facto eugenics in that it will affect people’s reproductive decisions at some level. Of course, having this as the stated intention is now taboo.

Adam

Dec 6 2016 at 8:15am

[Comment removed pending confirmation of email address. Email the webmaster@econlib.org to request restoring this comment. A valid email address is required to post comments on EconLog and EconTalk.–Econlib Ed.]

Maz

Dec 6 2016 at 8:52am

It was eventually understood that Social Darwinists had their Darwinism exactly backwards. Selection is reliable and relentless. If nature needs help, it is with variation. It is lack of genetic diversity that causes species to go extinct. Nature can’t select for a needed trait that isn’t there. There is no one genetic type that succeeds best in all possible environments. Genetically diverse populations are the most evolutionarily robust. Genetically similar populations are evolutionarily fragile.

One of the great misconceptions is that eugenics was somehow refuted intellectually and scientifically. It wasn’t. It went out of style simply because it became to be associated with Nazi atrocities. It wasn’t refuted.

On the contrary, our current knowledge of behavior genetics indicates that genetics is even more ubiquitously important and the environment even less important than the eugenicists of a 100 years ago thought. Moreover, there’s plenty of genetic variation to go around in any given population and there’s certainly no risk of running out of genetic variation because of any feasible selection schemes.

With better and better genomic prediction equations becoming available and embryo selection and genetic engineering advancing, eugenics is bound to make a comeback in a big way. If parents rather than governments make the choices there’ll be less risk for abuses, but, on the other hand, it will exacerbate inequality because the best eugenic methods will be available to those who can afford them.

Mauricio

Dec 6 2016 at 8:55am

Greg had it right. The podcast was incredibly thought provoking but I fear that a lot of what was said can be taken out of context and was lacking a more balanced argument.

I wonder how many associations with racism you are able to find when you dig deep into the conservative wardrobe. Smith and Mill, who weren’t racists and are now considered conservative economists can absolve any conservative from racism.

The point is not to defend or absolve one ideology or another, but my fear is that this type of explanation can be used to defend conservatism from a moral grounds perspective.

“Pervasive racism and a casual acceptance of Eugenics wasn’t the thing that separated the American progressives of this era from conservatives. It was the thing that united them.”

Mark Crankshaw

Dec 6 2016 at 11:12am

@GregG

I’ve got to push back on this point. No, the biggest terrorist threat in the Progressive Era was socialism and communism. Marx called for his “inevitable” revolution in 1848, Bismarck created the Prussian Welfare State to stave off a socialism revolution shortly thereafter. Socialism and Communism threatened to destroy the existing order by violently seizing control of the State. Lenin carried this violent threat to fruition in 1917. Eventually this hyper-statist philosophical cancer spread around the globe, sentencing hundreds of millions to a brutal and violent end. “Too much government power” has led to endless war, famine, and economic depredation on a gargantuan scale since Marx first penned his vile screed.

In contrast, the “anarchist” movement remained in the fringes, a few politicians were killed, perhaps. However, the “anarchist” movement never claimed the head of a single state. Millions have never been sent to their graves due to “too little government power”. A ruling elite has governed every country in the world, no matter of the right or left, for millennia.

It is my understanding that you believe that is so because society “wants” the government power exercised over them. Of course, I disagree, every instance of government power has been imposed on a subject class exclusively by force and ceaseless mental manipulation (propaganda and the indoctrination of “education”). Government power brings unearned riches and the ability to “make the rules” (in their favor, of course) to the ruling elite, be that the elite that surrounded Ceasar, Genghis Khan, or Barrack Obama. That’s why they impose their rule, that’s why there is the withering indoctrination, and why they get very violent to any that resist their rule.

In my eyes, your argument is the same as arguing that prisoners “need” and “want” a warden, prison guards, and thick prison walls for their “protection” and to provide “order” and “prosperity” for the inmates. I disagree. In my view, the State is nothing more than a mental prison into which we are born. We are told, from earliest childhood, that this is where we “belong” and ceaselessly told of the merits of prison life and all of the wonderful “services” and “protection” the prison staff “provides” for us. We are taught to fear “freedom”, our own and especially that of their fellow “inmates”.

Most of those born in this self-constructed mental prison are scarcely aware that any alternative can exist, and deeply fear that lack of ‘order’, ‘leadership’, and ‘protection’ provided by their mental prison were they ever to “be set free”. They fear a world without prison walls, without the warden, and without well-armed guards. I don’t approve of violent revolution of any kind. However, the “anarchists” at least could see a world exists outside of the mental prisons we have had built in our minds over the centuries.

Mark Crankshaw

Dec 6 2016 at 11:42am

I fully agree with Professor Leonard’s trenchant critique of the Progressive movement. I am a little surprised, however, that the unseemly philosophical and religious underpinnings should come as a surprise to anyone. Rothbard, von Mises, and Hayek have written extensively about these same loathsome attributes of progressives and socialist “intellectuals” and quite some time ago. Leonard has correctly pointed out that racism is, however, only one minor aspect in these elitist mindsets.

With all of the political philosophies I despise, of which “progressivism” is but one, I vehemently disagree with their characterization of the relationship between the individual and “the collective”. In the progressive view, as Dr. Leonard has pointed out, the “collective” exists outside and above the individuals that comprise it. Individuals, in the left-wing view, exist merely to serve the interest of the collective. I disagree, “collectives” should exist, as a mere tool, to further the interests of the individuals that choose to create it as a concept. Should it fail to do so, it is the collective, as a concept, that needs to be remorselessly dispatched.

Left-wing intellectuals (be they economists, philosophers or politicians) simply substitute their own individual will for that of the collective. The final invariable philosophical result: the leftist “intellectual” insists that all individuals must obey and serve the leftist “intellectual”. Hundreds of millions, perhaps billions if we count the needless wars, were murdered in this “service”, especially those who resisted the “intellectuals”. Self-serving doesn’t fully capture the full flavor of this malady, narcissism is much closer.

Mark Crankshaw

Dec 6 2016 at 1:17pm

@Bob

Clearly yes. However, I am not at all convinced that it is accidental. While “racism” may be the currently PC “thought-crime” to be most vilified at this time, I believe that the dark under-currents that infuses modern “progressive” thought goes far beyond mere racism. I find the “progressive” movement repellent not only because of the “soft-racism” of low expectations they often exhibit, but more so by the elitist “class” mindset they exhibit as well.

I’ve long considered much of the Welfare State as an admission of failure in the modern semi-socialist state. The economic “dead-weight” of a bloated military, bloated and retrograde education system, and bloated regulatory bureaucracy, the “socialist” aspects of modern Western economies, precludes providing jobs and opportunities for a large portion of the population. The slow growth and lack of jobs and opportunity has been chronic in Western Europe since WW II. The US has long ago imported this disease (though our Welfare State is augmented by a swollen prison population). The Welfare State is the “cost” we pay to support all these anti-market endeavors– it’s a bug not a feature.

Most political attacks on political opponents conducted by “progressives” today are filled with innuendos about the mental or moral “deficiencies” of those political opponents (even if they studiously avoid terms like “redneck”). The Left portray themselves as the superior class. More “scientific”, more “enlightened”, more “rational”, the very paragons of political virtue. The “progressives” ceaselessly esteem themselves as intellectuals (even Hollywood actresses with room-temperature IQs!) and moral crusaders. Anyone who speaks against their theories or question their morality are quickly labeled by many on the Left as irrational (hateful, racist), retrograde and/or monstrous (Nazi).

I disagree with “progressives” specifically because I disagree with many of the basic underlying philosophical and economic assumptions of “progressivism” or socialism and because I do not share many economic and political interests with many leftists. I do not despise the Left because they are irrational or monstrous (they are not). They act against my interest, and I will support acting against theirs if our interest conflict (which they often do). However, it appears to me, that the bulk of the Left will not concede that there can be serious problems found with their ideas, policies, morality and reasoning and so reflexively resort to name-calling and casting aspersions.

Nonlin_org

Dec 6 2016 at 3:14pm

@ Greg G

“Variation and selection are the two key concepts in Darwinism … As long as you have variation, the different varieties will survive in unequal numbers and that will drive evolution”

– so why insist on randomness? See, this is the problem with “evolution” – nothing about this concept is scientific. Or like Tom Wolfe puts it: the theory fails all five tests for scientific hypothesis: Observed? Replicated? Falsifiable? Predictive power? Illuminates other areas of science? “In the case of Evolution…well…no…no…no…no…and no”.

“Fitness is measured as successful reproduction, not mere survival”

– my comment was about survival of the species (whatever “species” means), not survival of the individual. The point is that you only measure survival and never fitness. Hence, there’s no such thing as fitness. Example: is the tall or the short guy fittest (for mankind)? And what about the other myriad differences between those two guys? You can never forecast fitness, hence there’s no such thing as fitness.

“Selection is not random”

– not only is selection non-random but it’s always done by intelligent beings (if you’re a lion, gazelle, a bug or bacteria) and it’s always purposeful. So “unguided”, “blind” selection makes no sense.

“Eugenics is in conflict with Darwinism because it assumes that, without human intervention, evolution is in danger of selecting for the organisms least adapted to the current environment … Eugenicists were attempting to make populations more genetically similar.”

– Danger to whom? Who cares about “danger to evolution”. No, this is a classic ‘us versus them’ story in which Eugenicists care about “us” (meaning them) not some nonsensical “danger to evolution”. Forget their declared goal of “improving the human population” – many people would say whatever to reach their actual goals. And why would you care about “robust evolution”? You’re not God, your lifetime is limited, and Earth will be just fine with or without you.

Madeleine

Dec 6 2016 at 4:52pm

@Nonlin_org

Eugenics is exactly to Darwinism what crony capitalism is to the free market: it involves a central power disrupting the formation of an emergent order to pick an outcome which is politically preferable. It is inherently corrupt because the central planners will quite literally have “skin in the game” (pun intended).

I think it should be of no surprise that central planners prefer Eugenics to natural selection. It’s central planning, after all! The podcast explored that quite well.

As for why we should care? Well, corruption sucks, first of all. Secondly, nothing says “nanny state” more than interfering in that sort of ultra-intimate role. Thirdly, who does not recoil in horror at the Chinese forced abortions? The mass sterilization of Africans against their will? I am going to go against the prevailing moral relativism that seems to have infected my age group (I’m 25) and I will say that I believe in moral absolutes, a concrete right and a wrong. And there is very little that strikes me as more clearly wrong than eugenics programs. I believe I would say that even if I had never heard of the Nazis.

Seth

Dec 6 2016 at 6:14pm

@Nonlin_org

That’s not Darwinism.

‘Survival of the fittest’ is not the struggle between weak and strong, though it is often interpreted that way.

It’s that things that are best adapted to the conditions present in an environment are more likely to reproduce and carry on.

Think less about lions eating gazelles (even though that has happened for a long time, gazelles are still around) and more buggy whip (which was a successful product for a good amount of time in modern history, but wasn’t well adapted to maintain its sales levels when the conditions of the market for transportation shifted away from horse drawn buggies).

Eugenics is loosely based on the same misunderstanding of ‘survival of the fittest’-Darwinism that you have.

Michael Byrnes

Dec 6 2016 at 6:14pm

Maz wrote:

I think that one of the lessons we will learn when better and better genetic engineering technologies become available, is one economists could have told us a long time ago: